In November 2023, Jonathan M. Katz wrote in The Atlantic about Substack’s Nazi problem. He argued that the platform has become a home to white supremacy and anti-Semitism, and that the platform profits from this activity. Following the publication of the Atlantic article, more than 200 writers on Substack signed an open letter to the company asking them why they are platforming and monetizing Nazis (Substackers against Nazis).

Here at Insight Monitor, we are anti-Nazi. (Apparently this needs to be said in 2024.) But we are also pro-inquiry, and wanted to know exactly what Substack’s Nazi problem might look like, how much money Nazis might be making from their newsletters, and how Substack itself is profiting from this content. Basically: we wanted to qualify and quantify this problem in order to provide evidence for policy recommendations.

For those of you who aren’t subscribers, here’s the TL;DR:

Nazis on Substack might make millions of dollars per year, with some creators making hundreds of thousands of dollars

Substack itself probably makes hundreds of thousands of dollars per year on Nazi content

Substack’s algorithm creates a network of Nazi substacks by recommending similar content

We should not give Nazis money: Substack should demonetize and de-prioritize these newsletters (at the very least)

GIFCT and Tech Against Terrorism should engage with Substack to help them develop better policies and practices

States should consider legislation and regulations against the monetization of hateful content (ideally platforms do this themselves…)

Yesterday (8 January 2023), Substack announced that it would be removing Nazi publications from the platform. This is not a new policy — but rather a reconsideration of how it considers existing policies. The removals only apply to “credible threats of harm”. The application of the policy applies to five publications, and none of the publications removed had paid subscriptions enabled, and they accounted for about 100 active readers.

This does not address the problem. Our dataset of Nazi content identified 75 publications with over a 100,000 readers, a significant proportion of which were monetized.

Subscribe to read more about how we came to these conclusions and our evidence-base:

How we found Nazi newsletters

To find Nazi newsletters, we initiated our research using the publications of known white nationalists and neo-Nazis, for example, a newsletter mentioned in the “Substackers Against Nazis” controversy. We snowballed (expanded our sample) using Substack’s own suggestion algorithm, including dozens of suggested Substack publications in our initial dataset.

We also used subscriber lists to identify possible newsletters for inclusion. When newsletters had a low number of subscribers, we were able to use these lists to identify further newsletters that used hate-promoting iconography or language, and included these in our broader sample for further assessment against our criteria.

This is not an exhaustive examining of the Substack platform for Nazi material; instead, it is a sample in a broader population. The actual number of Nazi newsletters on the platform is unknown.

Inclusion Criteria

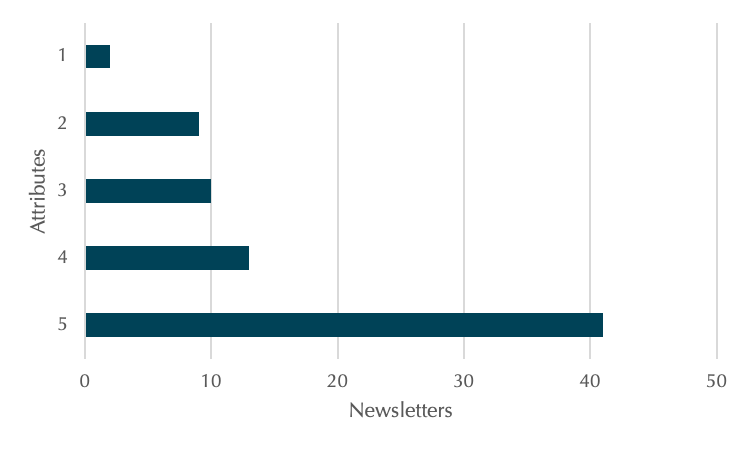

While we looked at nearly 100 publications, we analyzed the written content and imagery from 75 Substack publications (newsletters) whose contents clearly fulfilled one or more of the following attributes:

The publication uses Nazi symbols, terms, or slogans or explicitly defends, promotes, or celebrates Nazism.

The publication defends, promotes, or celebrates Adolf Hitler or other historic Nazis, or else defends or celebrates the Holocaust.1

The publication defends, promotes, or praises individual white supremacists or neo-Nazis.

The publication promotes White Supremacy or White Nationalism.2

The publication promotes antisemitism.

Evaluation

For each newsletter in the initial dataset, we looked at recent or pinned article titles and imagery against our inclusion criteria. Some of the newsletters initially included were excluded as they failed to meet any of our inclusion criteria, resulting in a final dataset of 75 Nazi newsletters.3

We also used keyword searches within the publication to determine inclusion and to analyze the content. Keywords promoting antisemitism and National Socialism included “Hitler,” “Jews,” “Holocaust,” and “ZOG” (Zionist-Occupied Government, a conspiratorial and antisemitic term commonly used by neo-Nazis). Additionally, keywords promoting white supremacy and white nationalism included “Blacks,” “white,” “race,” and certain anti-Black slurs.

While in many cases publications in our research promoted both National Socialism and white supremacy, 20 publications promoted white nationalism or extreme antisemitism without explicitly praising National Socialism or Nazism by name and without defending, denying, or celebrating the Holocaust or the actions of Nazi Germany in the second World War. At least five of these publications included articles by authors who were known to promote or defend Nazism outside of Substack.

In total, we found:

1. 45 newsletters used Nazi symbols, terms, or slogans or explicitly defend, promote, or celebrate Nazism.

2. 51 newsletters defended, promoted, or celebrated Adolf Hitler or other historic Nazis, or else defended or celebrate the Holocaust.

3. 65 newsletters defended, promoted, or praised individual white supremacists or neo-Nazis.

4. 69 newsletters promoted white supremacy or white nationalism.

5. 60 newsletters promoted antisemitism.

Over 40 publications included all five of our attributes, while only a few newsletters included only one of our attributes.

This categorization was based only on free material. We did not subscribe to any of these newsletters to identify further extremist or violent content. As such, this likely under-states the level of extremism / Nazi content in these newsletters, as authors might put the most extreme / inciting material behind a paywall.

Determining Monetization Levels

As readers of this newsletter know, creators who publish on Substack can choose to monetize their newsletters with a variety of subscription plans for their audience at monthly or annual rates. Additionally, publishers can choose to set a “Founding Member” subscription rate for their publication, which is typically more expensive than a standard subscription. A publisher can also let subscribers donate more money through the founding member option. While any Substack publication can be subscribed to for free, a publisher can choose to limit specific content to paying subscribers.

The exact number of paid subscribers that a Substack publication has is not available publicly. However, “bestseller badges” appear on Substack authors’ accounts, indicating authors with at least 100, 1000, or 10,000 subscribers. (It is possible to hide this badge.)

In our analysis, we used this publicly-available information to estimate minimum and maximum numbers of paid subscribers for each publication based on their bestseller badge (or lack thereof) and determined what the minimum and maximum amount of money the author could be receiving from their paying Substack subscribers.4

Further, substack claims 10% of a publisher’s subscription payments as platform fees, while credit card processing fees tend to claim an additional 3 to 5% of payments.

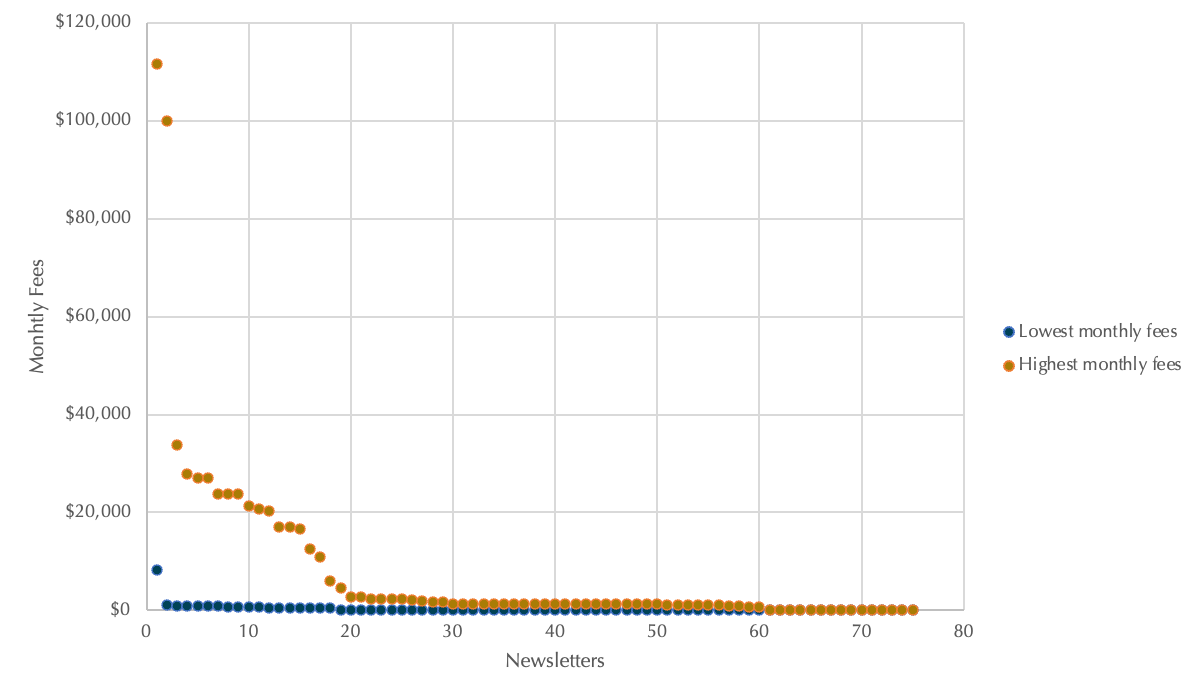

89% of publications including in our analysis had some option to monetize their content. However, the distribution of monetization is highly uneven, with some newsletters making little to no money, and others making (potentially) hundreds of thousands of dollars per year.

One particular publication that espoused extreme antisemitism, at one point mocking a fictional Jewish person as “Jewberg,” and that defended contemporary white nationalism, had at least 1000 paying subscribers. This newsletter might be generating between $87,000 and $1,000,000 per year. (The reality is likely somewhere in the middle — million-dollar newsletters are rare, but not impossible.)

Another newsletter in our sample displayed Nazi iconography, identified itself as antisemitic, and claimed that “most blacks [sic] don’t have any brain matter” in “the part of the brain that deals with logic, sound decision-making and higher-thinking in general”. This newsletter generated between $8,200 and $343,000 annually.

The Network Problem

In addition to the monetization of hate, Substack’s feature of recommending similar publications to readers provides hate-promoting publications with a valuable tool to reach new audiences. In our research, we used this feature to discover neo-Nazi and white supremacist’s newsletters that were not previously known to us. While this aided our research, it demonstrates that Substack users viewing the same publications are likely to be recommended similar materials.

The Profit Motive

In addition to the ethical controversies about the monetization of hate content, this analysis raises the issue of Substack’s culpability in allowing for an easy method for promoting hate content. According to analysis conducted using the search engine optimization tool Moz, Substack articles are relatively highly prioritized in search engine results, such as Google searches. While the search engine optimization of hate-promoting platforms varies, many independent blog sites and traditional forums frequented by hate movements are known to be low-priority in search engines. For example, the prominent neo-Nazi forum Stormfront has a domain authority of 65, which is significantly lower than Substack’s score of 92 (both measured at the time of publication).

Even in today’s social media environment, where hate speech is rampant on many major platforms, the extreme nature of many of the newsletters leads us to conclude that Substack is a uniquely large platform for financing hate content.

While many prominent neo-Nazis subscribe to Twitter/X Blue (for example former National Youth Front leader Angelo John “Lucas” Gage has amassed over 220,000 Twitter/X followers) — and as such are eligible for monetary gain for their Tweets promoting National Socialism and hate speech, the nature of how Twitter/X finances popular accounts means that payments for content can be inconsistent.

Conversely, financing through Substack is direct. As such, it can provide much more reliable, long-term funding than larger social media outlets with comparably relaxed content moderation policies.

These funds are important for these extremist content creators. Many of them have been publicly outed as neo-Nazis, white supremacists, and promoters of hate. These creators might find it difficult to obtain gainful employment because of the content that they produce, making them reliant on their Substack revenues. In other cases, they might be driven to produce more hateful content in order to drive revenue.

In our analysis, some of the newsletters with the most Nazi attributes were also the most highly monetized newsletters, which raises a concerning correlation between extremism and money.

Finally, it’s worth noting Substack’s profit motive. While our estimates of revenue generation for these newsletters is crude, there is no doubt that Substack is profiting from this content. We estimate that Substack is generating somewhere between $24,000 and $724,000 in annual revenue from these newsletters — and our sample of Nazi newsletters is far from an exhaustive look at hate on the Substack platform.

The policy solution

Giving money to Nazis is not good. Without delving into the free speech issue (itself worthy of many newsletter articles), here at Insight, we tend to think that people should not be allowed to make money from hate. We agree with some of the proposals put forward in this thoughtful newsletter from Platformer that these newsletters should, at the very least, be demonetized. They should also not appear in recommendations or be promoted by Substack in any way.

If Substack is unwilling to take action, then it might be worthwhile for concerned newsletter readers to engage with Stripe, the payment processor, as some of these newsletters might breach their terms of service.

There are other options as well, some of which involve state intervention and new rules and regulations around monetization of hate content, which will be time-consuming and cumbersome to develop and implement. (And in the case of Substack, a US-domiciled company, will likely run into constitutional challenges.)

There’s also likely a role here for GIFCT and Tech Against Terrorism to engage with Substack and help the company develop better policies around the monetization of hate.

The easiest and best way forward is the one that, to date, Substack has refused to do: demonetize Nazis.

For now, Insight Monitor will remain on the Substack platform. We agree with Platformer that no platform is perfect. However, this is exactly the type of issue that will be weighed in our consideration of the future of this newsletter. Feel free to let us know what you think in the comments.

Want to learn more about how violent events are financed? Check out our analysis of the financing of January 6th:

© 2023 Insight Threat Intelligence Ltd. All Rights Reserved.

This newsletter and its contents are protected by Canadian copyright law. Except as otherwise provided for under Canadian copyright law, this newsletter and its contents may not be copied, published, distributed, downloaded or otherwise stored in a retrieval system, transmitted or converted, in any form or by any means, electronic or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyright owner.

For the purposes of this attribute, prominent National Socialists including Joseph Goebbels, Alfred Rosenberg, Heinrich Himmler, and Francis Parker Yockey were considered “historic” Nazis. Additionally, promotion of historic Nazi sympathizer Charles Lindbergh was included when the publication specifically defended Lindbergh’s affection for Nazi Germany.

Though some publications did not promote White Nationalism by name, publications that called for the relocation or genocide of specific groups of people to achieve a goal of a Caucasian, “white,” or “Aryan” ethnostate were labeled as publications promoting White Nationalism.

This is almost certainly a small sample of the Nazi / hate problem on Substack. We are but one small team doing an initial scoping exercise. There is certainly room for more robust and detailed analysis.

This is not perfect: it is possible for creators to gift paid subscriptions, meaning that they generate no revenue from those “paid” subscribers.