Terrorist Financing through Charities

And non-profit organizations

In May 2021, the International Civil Liberties Monitoring Group released a report on The CRA’s Prejudiced Audits. The report outlines how Canada’s supervision and monitoring of charities in Canada evolved after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, and how that work has been carried out largely in secret. While I took issue with some of the facts and framing in the report, it highlights the need for better understanding of how charities are exploited by terrorists for financing, and greater precision in our language about charities and terrorist financing - because this affects how we describe and analyze potential terrorist financing risks, and the policies we develop to counter them. This is true globally!

As part of their use and abuse of a variety of different types of organizational structures, terrorists make use of charities, non-profit organizations, and charitable causes. This can include registered charities, religious entities or organizations, and charitable fund-raising calls (including through crowdfunding websites or social media). While the use and abuse of the charitable sector has been somewhat over-stated as a terrorist financing method, terrorists have and continue to use charities to raise funds. This remains an area of risk for terrorist financing.

Charities and non-profit entities help terrorists raise funds, but also move funds into and out of higher risk jurisdictions. In some cases, they can also provide terrorists with a cover (through employment or association).

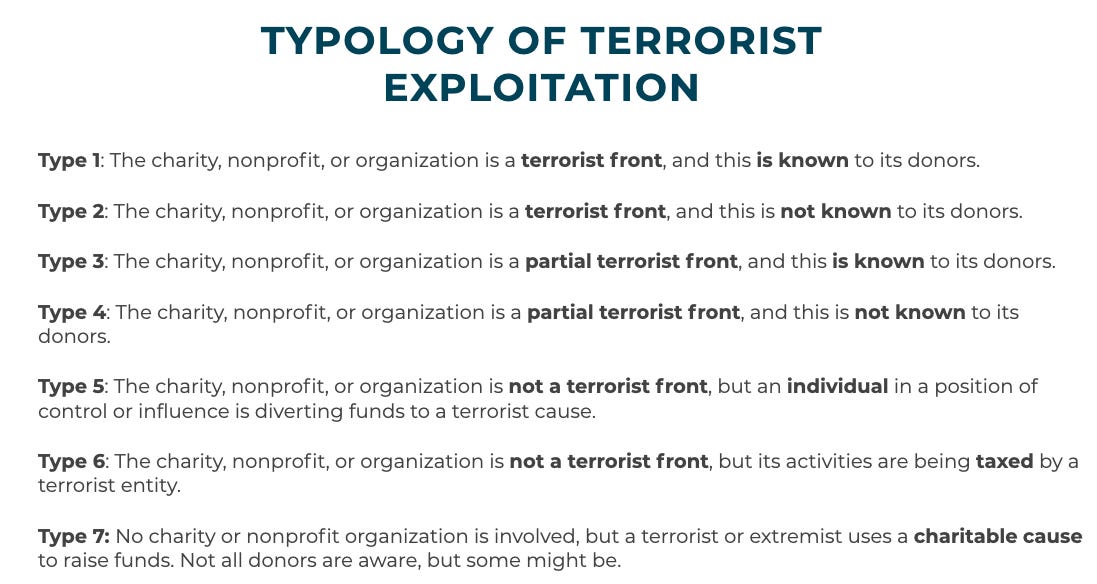

There are several types of charities and non-profit organizations that are used by terrorists, and in a variety of ways:

wholly owned organizations that are fully complicit and aware of their activities

those that occupy more of a grey zone, in that they probably have a good idea of where the funds are going but have plausible deniability (even if that deniability is met with significant skepticism)

those that are more or less legitimate but have an officer or person in a position of control or influence that can divert funds to different terrorist groups or cells those used by outsiders without any internal knowledge or awareness

For my forthcoming book on terrorist financing (which I’ll link to as soon as it’s available for pre-order), I developed a typology of the seven main ways that terrorists abuse charitable activities. This involves differentiating the organization’s level of complicity and that of the donors. The most important thing to remember here is that rarely is an organization a total terrorist front; instead, most of the time, one or more people in positions of control or influence are the problem. As such, it’s imperative that we investigate the individuals rather than the organization itself.

In terms of the prevalence of terrorist financing in the charitable sector, it’s limited. Only 20% of terrorist organizations have a confirmed use of charitable fundraising or exploitation through charities. Operationally (attacks, plots and other activity) speaking, only 4% of attacks were financed in some way through the charitable sector.

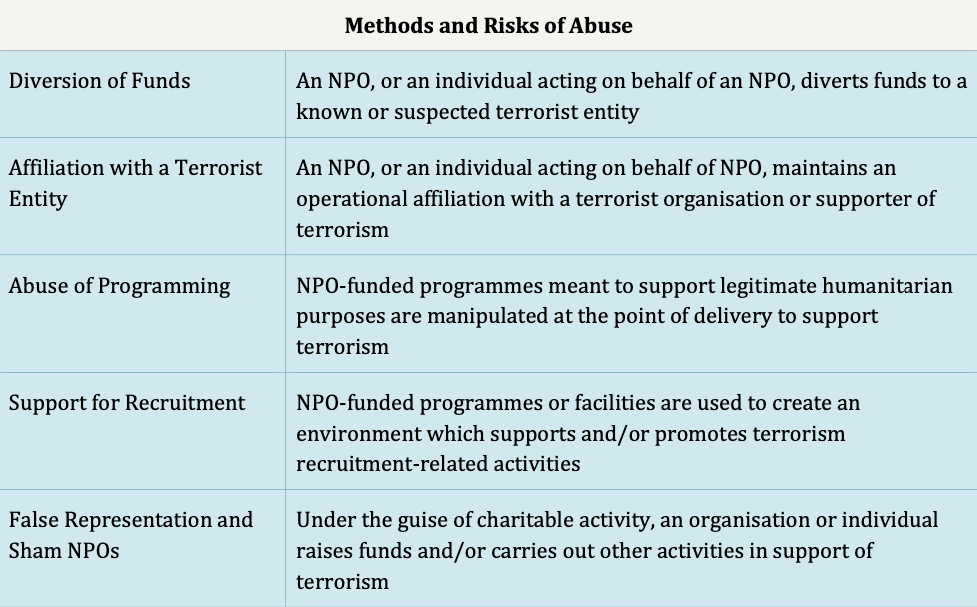

The Financial Action Task Force (FATF) outlines more types of abuse and risks for the sector, above and beyond just terrorist financing.

Using precise language when we talk about terrorist financing through the charitable sector is critical. Key questions to ask include:

Is the entire organization complicit, or are we looking at particular individuals?

Are the donors aware?

Can we tie this activity to terrorist financing, or are we looking at financial (or other) mismanagement more generally?

How can we support charitable organizations to make them more resilient to financial abuse?

How can we avoid creating an undue burden for charitable organizations, especially small or grass-roots ones, and yet still prevent abuse by terrorists?

We have a long way to go internationally before we strike the right balance of risk and suspicion with regards to the charitable sector, and using precise language and terms is only part of the battle.

© 2022 Insight Threat Intelligence Ltd. All Rights Reserved.

This newsletter and its contents are protected by Canadian copyright law. Except as otherwise provided for under Canadian copyright law, this newsletter and its contents may not be copied, published, distributed, downloaded or otherwise stored in a retrieval system, transmitted or converted, in any form or by any means, electronic or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyright owner.