They’re Washing Billions. You’re Paying the Price.

Money laundering makes us less safe and poorer. There's a simple solution.

I’m often asked why money laundering matters, and when I try to explain, I’m met with a glassy look. I’m clearly failing at this. Maybe that’s because it seems obvious to me: money laundering is bad because it incentivizes crime, which harms people. And yet….that explanation has failed to capture people's attention (including Canadians).

Today, I will explain why everyone should care about money laundering: It directly impacts our well-being, both physically and economically. Hopefully, by the end of this article, you’ll be raging mad that anti-money laundering isn’t at the top of the political agenda in your country.

Enabling Crime

The first issue is a fairly obvious one, although the direct impacts on personal well-being are one step removed from traditional crime, making it harder to understand. A lot of crime (maybe most?) is motivated by profit. Drug traffickers sell drugs to make money, thieves and fraudsters steal money and goods for profit (or to re-sell for profit), and human traffickers buy and sell humans to make money. It’s easy to understand the negative effects these crimes have on people: anyone who has ever been a victim of fraud or theft or had someone they know be victimized in this way understands the sense of insecurity even a minor incident can create (let alone the violence that often accompanies these activities). We all want less crime.

It’s harder to see the direct impacts of “white-collar” crime. Tax evasion, embezzlement, and insider trading are all forms of theft from governments, businesses, and individuals that ultimately make us all poorer and a select few much, much richer. Tax evasion is theft from the government (and, by extension, its citizens). Embezzlement is theft from a company or organization (and its shareholders, employees, or investors), and insider trading is theft from investors (by using confidential information to make better deals or advantageous trade to the detriment of people who don’t have that information).

Think about the case of Enron. Back in 2001, the company declared bankruptcy after officials embezzled tens of millions of dollars, causing the company to collapse. This destroyed the pensions and savings of thousands of people, including pensioners and shareholders of the company. Image a similar situation with your investments: would you be okay with losing $5,000, $10,000 or more to an embezzlement scheme? I know I wouldn’t.

Anyone who invests in public markets will recognize the impact this can have: lower profits and unfair wealth distribution. But what about people who don’t invest in public markets? Are they impacted? They are if they have any pensions or state benefits. For instance, in Canada, every Canadian is a pension holder in the Canada Pension Plan (CPP). The CPP investment board invests the plan's money from employers and employees. So, ultimately, every Canadian is an investor in public markets. So-called “white collar” crime affects everyone, but the more money you have in public markets and pensions, the more impacted you are.

So, we can agree that these crimes are bad, but what about the role of money laundering? Once criminals have gotten money from these activities, regardless of whether it is human trafficking or insider trading, they need to hide the source of funds. This is because if they don’t, as soon as law enforcement realizes what they are doing, they can freeze and seize those funds. Criminals have to hide the source of funds, making it hard for authorities to determine where the money came from. This is money laundering and is what makes these types of crimes profitable. Without money laundering, it would be easy for law enforcement to remove the profit motive of crimes. Would a drug dealer continue to sell drugs if the police could just come along and take all their money? Would people under-report their income and use elaborate schemes to make it appear like they made less money than they did if law enforcement could identify the discrepancy and seize unreported income? Probably not.

You’re probably thinking: yeah, maybe these activities have a direct impact on my bottom line, but that impact is spread out across the entire population, so I’m only harmed a little bit. And maybe that’s true. And if you’re willing to let criminals make money off you because tackling money laundering is hard, I guess that’s your choice. But what happens if a country’s money laundering problem becomes so big that it creates other harms, like distorting markets and undermining legitimate business?

Market Distortion & Manipulation

When criminals have a large amount of cash to launder, they often make decisions that are not entirely profit-motivated. These decisions are mediated by the difficulty they face in laundering their money. They might pay above-market prices for goods when they obtain other benefits, like a seller willing not to ask difficult questions about the source of funds for things like cars, jewellery, or even real estate.

For instance, if several money launderers or criminals operate in a region (say, entirely at random, British Columbia), they might find real estate attractive as an investment and method to launder funds. When a lot of dirty money is invested in a regional real estate market, it can create a wedge between local incomes and local real estate prices. The criminals pay more than the fair market value for a property because characteristics of the market (maybe banks, mortgage brokers, and real estate agents who aren’t looking to confirm the source of funds) create benefits for them beyond simply owning the property: they get the property, but they also get an asset they can use to explain their wealth.

In a few years (or months), the criminals might sell the property, then their source of funds becomes “real estate investing”.

In some cases, they might sell the property to other criminals for an above-market value (again, because of the benefits I described above), making a profit and enabling other criminals to enter this market. To some extent, this hypothetical scenario creates a pyramid or ponzi scheme: sustaining the inflated market requires an ongoing supply of new investors paying these high prices. Unfortunately, demand for houses is inelastic in many markets, meaning these prices stay high. Any regular person trying to enter the market now has to pay these new, inflated prices and hope there isn’t a market correction. The money launderers can take the hit from a correction, but can retail investors or families? Probably not.

Unfair Competition

Money launderers don’t just invest in real estate; they seek any asset that can hold (or appreciate) in value. They’re also looking for investments that can be used to explain large quantities of cash. For instance, coffee shops, bars, restaurants, and laundromats are all valuable places to park illicit cash. Not only can you get access to a real, tangible asset (which might be helpful as collateral for loans for other legitimate business ventures), but you get access to a business that generates a large volume of cash. Simply inflating sales can be enough to hide an influx of illicit cash: instead of reporting the sale of $2,000 worth of coffee one morning, money launderers might report the sale of $3,000 worth of coffee, stuffing $1,000 worth of cash into the register and calling it “sales.” For one day, this might not be that helpful. But if you did the same thing every day across multiple locations, you might have a successful method of laundering money. For scams and other types of crime, the internet and cryptocurrency have supercharged money laundering activity.

And what about the people on the same street who are operating coffee shops that aren’t money laundering fronts? They might have a hard time competing with the lower prices of these establishments because to do the kind of volume that the fronts want to do, they will probably have slightly lower-than-market-rate prices. The fronts aren’t worried about making rent; they’re worried about creating a plausible front to move cash. Anyone who has ever operated a business can understand how this activity can create unfair competition.

Undermining Trust in Financial Institutions

We’ve probably all heard the story of TD Bank. In the US, the bank was fined US$3 billion after pleading guilty to money laundering. At least one of the schemes involved 5 employees laundering drug proceeds. TD Bank has basically become a punch line for jokes about money laundering in Canada and the US. While the direct effects of this are difficult to measure (I have yet to hear of many Canadians moving their money out of TD because of a lack of trust), if the problem becomes more systemic, citizens will stop holding cash and assets in their domestic financial institutions. This, in turn, reduces those institutions’ ability to issue mortgages and other forms of credit.

Economic Distortion

Money laundering distorts economies by injecting large volumes of illicit funds into legitimate financial systems, often fueling artificial growth. As these illicit investments inflate economic indicators, there is reduced political and institutional incentive to address the underlying criminal activity. (For instance, this might be the case in some countries’ financial and real estate sectors.) However, this false growth crowds out legitimate enterprises, distorts market competition, and undermines long-term economic stability. Over time, such distortion attracts further illicit activity, entrenching criminal networks and increasing the likelihood of violence as these groups seek to protect their interests and expand their influence. The result is a warped economy where crime thrives, accountability weakens, and legitimate development is compromised.

Reputational Damage Turns Concrete

Some of you might still be thinking, “So what”? If there’s money to be made, it can’t be all bad, right? Well, you’d be right until you’re wrong. See, there’s this little thing called the Financial Action Task Force and international sanctions. States might apply sanctions to countries with serious criminal and illicit finance problems. For instance, the US designates some countries as jurisdictions of primary money laundering concern and, in exceptional cases, can prohibit US financial institutions from transacting with the jurisdiction. Being cut off from the US financial system seriously affects business and individual investors. And the Financial Action Task Force can place countries on its grey or black list. While this is not a direct sanction, in practical terms, being placed on the grey list reduces foreign direct investment and increases friction for individuals doing business internationally by reducing correspondent banking relationships and transaction speed. When countries are placed on the blacklist, they can effectively lose access to entire markets like the European Union and North America.

Crime in Canada

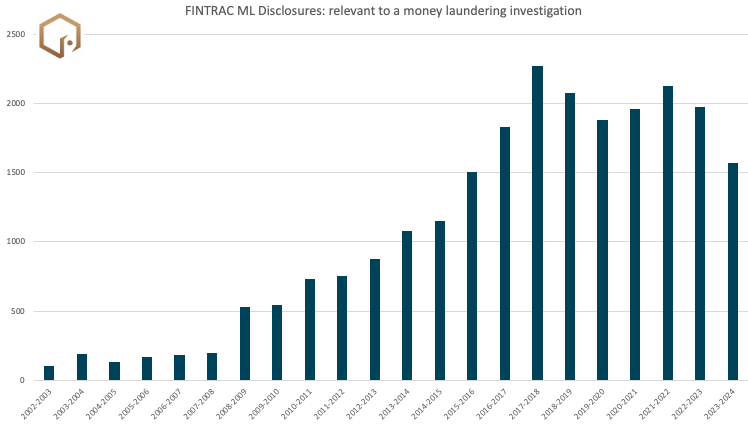

The unfortunate problem in Canada is that there has been an increase in profit-motivated crime over the last decade. Police-reported cybercrime, as well as police-reported organized crime in Canada, have all increased dramatically.1 Some of that increase is visible in information released by FINTRAC. Since 2001, FINTRAC has shared over 20,200 disclosures that it found relevant to a money laundering investigation. I’ve argued here before that FINTRAC disclosures are a very rough indicator of criminal activity in Canada (and we shouldn’t expect a 1:1 relationship between disclosures and prosecutions). However, some estimates suggest that Canada has a $50 billion money laundering problem (or roughly 2.4% of our GDP). Similarly, FINTRAC indicated that it disclosed $44 billion worth of transactions that it suspects are related to money laundering last year. This, along with other qualitative information about the prevalence and role of professional money launderers, suggests that Canada has a growing, not diminishing, problem with money laundering and crime. And increasingly, that is going to cost you and me money and, ultimately, our safety and security.

What we can do

Look, investigating and prosecuting money laundering is hard. I do a lot of work explaining why that is (and why it’s especially hard in Canada). I don’t have time to go into all of the reasons right now (but let me know if you want a separate article on that. I might write it.) Let me assure you that policy solutions exist. However, the thing that has to happen to make policies a reality is public pressure. Right now, political parties have almost no incentive to address the situation. They’re enjoying the benefits of illicit finance being invested in our economy and hoping someone else will be in power when our chickens come home to roost.

But I care about this, and I think you should too. I don’t want more crime in Canada, and I certainly don’t want criminals profiting from me, taking money from my investments or retirement, and generally making me poorer. Imagine if we could tax some or all of that money. I’d certainly take a 10% cut of $50 billion. It might even help buy us some fighter jets or something.

The good news is this: if money laundering is a $50 billion problem in Canada, the solution isn’t investing $50 billion in law enforcement (and related initiatives). I’m not even sure that it’s a $1 billion investment. Even a hundred million would probably yield a good return in reducing crime, seized assets, deterring professional money launderers from setting up shop, and maybe slowly unravelling some of the market-distorting effects that might have happened in Canada.

So when an election candidate comes to your door and says they want to make the housing market more affordable, ask them what they’re doing about money laundering. And when they say they want to be tough on crime, ask them what they’re doing about money laundering. And when they say they want to support small businesses and grow Canada’s economy, ask them what they’re doing about money laundering.

Investing in our ability to combat money laundering comes at a price I’d happily pay. What about you?

Statistics Canada reports significant increases in both of these types of crimes between 2016 and 2023.

Such a great breakdown of the many ways money laundering damages our society! If Canadian governments and law enforcement agencies ever got serious about tackling the problem, the benefits would be enormous. Unfortunately, it’s so easy for them to turn a blind eye.