Hello Insight Monitor subscribers! After six years of building, cleaning, and analyzing, I’m finally ready to share a new dataset that changes the conversation on terrorist financing. This isn’t just another trends piece. It’s evidence-driven, assumption-busting research that brings clarity to what’s actually happening in terrorist finance today. The goal? Cut through speculation with solid data. Provoke debate. Challenge what we think we know. Check it out, share it widely, and if you haven’t already—subscribe to stay ahead of the curve. This is just the beginning.

Understanding Trends in Terrorist Financing

This research is driven by a grievance. It irks me endlessly when trends are presented in academic research or media commentary as “new” or “increasing” without any evidence to support these assertions.

So I decided to put my money where my mouth is and create the evidence I would need to make statements like that. Eight years ago, I started collecting “cases” of terrorist financing. These are incidents of individuals or groups engaging in terrorist financing activity from around the world. Readers of the Global Terrorism Financing Report will find this framing familiar: we use this case approach to populate that report.

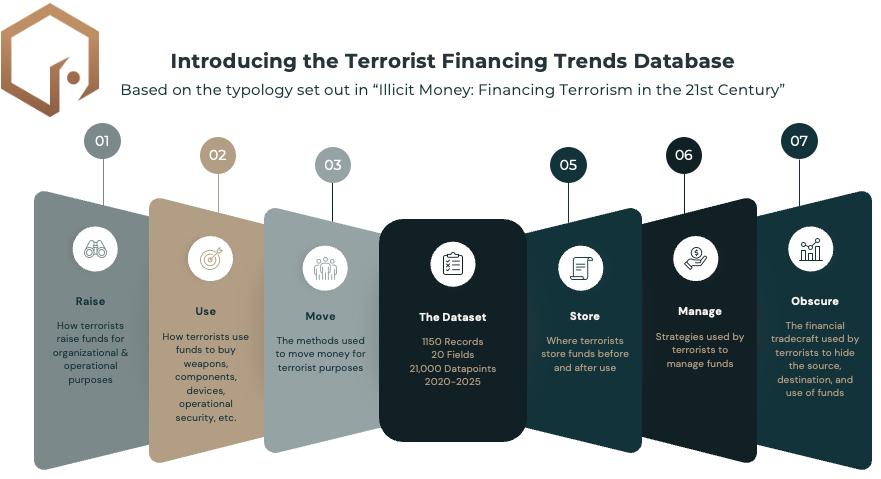

In our data, a case of terrorist financing is any reported incident of terrorist activity financing – that is, any financial activity that was used to support terrorist activity. This activity is further broken down into six mechanisms: how terrorists raise, use, move, store, manage, and obscure the source, destination, and use of those funds. Again, this will feel familiar to many readers, because it’s the typology I developed in Illicit Money. We further capture information on the methods used within each of these mechanisms, from things like cash couriers to hawalas to cryptocurrency and much more.

Our definition of terrorism is equally important to understand. We use a definition I developed for both Women in Modern Terrorism and Illicit Money, which draws heavily on the Canadian Criminal Code definition of terrorism. For us, it’s less about the ideology or group and more about the activity. In short, we’re looking for cases of violence (planned or disrupted) with a religious, ideological, or political motivation, intended to influence or intimidate a population (this can be as few as one person, such as a politician, or as many as an entire country).

Terrorist Financing Analysis

Our terrorist financing analysis course caters to researchers, intelligence, law enforcement, and compliance professionals, helping them learn about terrorist financing and analyze suspicious patterns to disrupt terrorist activities more effectively. Sign up today to grow your counter-terrorism expertise.

Data Collection

We find these cases in open sources: in things like media reports, when our friends at CourtWatch report on indictments, from government reports, etc. We don’t use covert methods to collect this data, but we will include information released publicly that might have used covert methods.

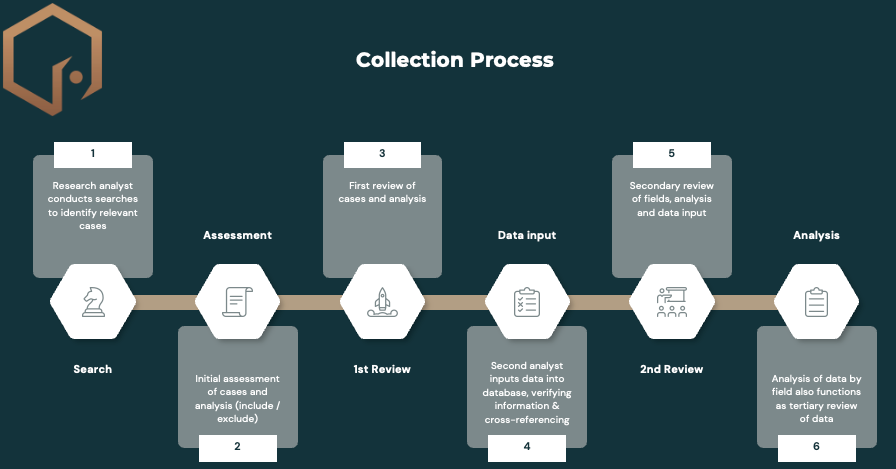

We use a robust method to validate the data. First, a researcher finds all the relevant cases and writes them up for the Global Terrorism Financing Report. I then review the draft report and make any required deletions (for things that don’t fit our criteria). A second analyst then inputs these cases into the database, where I review them again. Finally, I do a tertiary review when I pull the data and conduct analysis.

Ultimately, this has yielded over 21,000 data points across 1150 records and 19 fields. These fields include coding for group, country, a text description of the case, the methods and mechanisms used, and of course sources. While there is data from 2018 onward, we only use the data from 2020 and onward because it’s more reliable. (It’s when I hired staff).

What We’ve Found

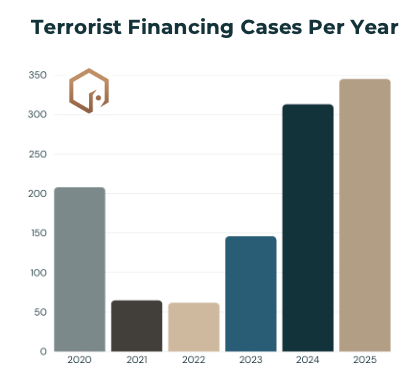

On average, we capture about 190 cases per year, although 2021 and 2022 had the lowest amounts of data. This might be due to a lack of terrorist financing, a lack of disruption/detection of terrorist financing, or other factors. In my experience, data blips like this generally result from a combination of factors.

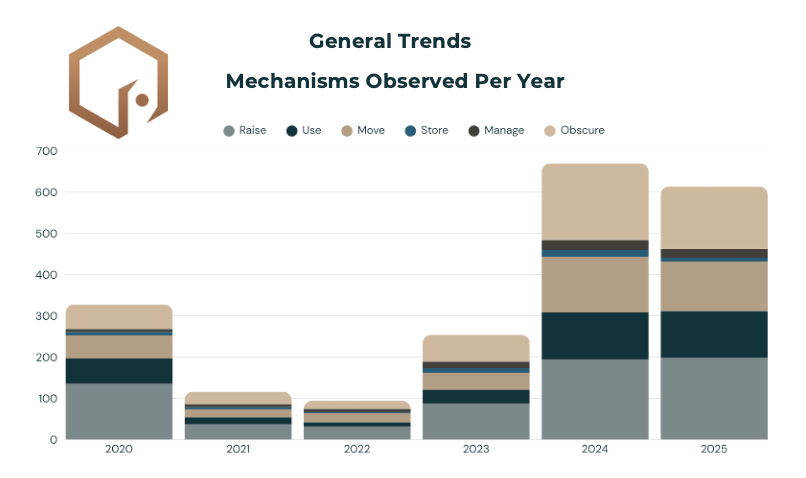

Each year, we usually see the most reporting on how terrorists raise money. However, we also see lots of information on how they’re hiding that money. Less often reported is information on how terrorists are managing and storing funds. These mechanisms are likely harder to detect and less sexy to report on. However, they’re still critical for understanding (and more importantly, disrupting!) terrorist financing.

The Limitations

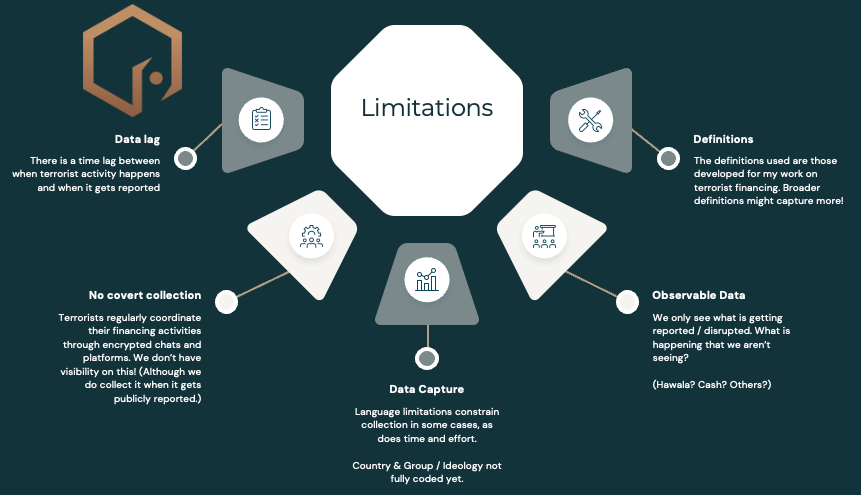

There are plenty of limitations with this dataset (like all datasets). Firstly, as mentioned previously, there is no covert collection. This means we are certainly missing some trends and methods in the world of terrorist financing. Secondly, there are limitations to the data we can capture. Some of this is due to language, but it’s mostly due to time limitations. As this project is entirely funded by my company, Insight Threat Intelligence, I can’t assign unlimited resources to data collection.

Reader support for Insight Monitor goes directly to supporting this project, so thank you to all our paid subscribers who have made this possible!

Thirdly, the data is limited to observable and reported data. We don’t have visibility (through this data collection method, anyway) of harder-to-identify terrorist financing methods. For instance, I think that the use of hawala is likely underreported in this data. Other methods and mechanisms are also likely underreported. Fourthly, there is likely a lag in the data in terms of when we see trends emerge. Disruptions, arrests, prosections, and even investigative journalism all takes time. This time creates a lag between when a terrorist financing method or mechanism occurs, and when it gets reported publicly. So while this is the only dataset like this in the world, it does have a time lag.

And finally, definitions matter. While I have confidence in the definitions that we use, a broader definition of terrorism would capture more information. A narrow definition might yield more nuanced results. Part of the way we correct for this is through the use of filters and the ability to exclude entire classes of cases, like the recently listed criminal organizations. (While I think these do meet the legal threshold for listing as terrorist entities in Canada, I fundamentally think they operate differently from terrorist groups; as such, they should be analyzed separately.)

These limitations might seem daunting, but for me, it’s really about properly contextualizing our findings. We keep these limitations in mind as we write, so we never get out ahead of our skiis in our analysis.

Next Steps

If you stuck with me this long, that means you’re very likely a huge data nerd. Thank you! This series is right up your alley. There’s lots more to report on, so stay tuned for the next edition of the series on Trends in Terrorist Financing. You will see separate newsletters outlining how terrorists raise, use, move, store, manage, and obscure their funds, as well as a summary newsletter on key findings. We will likely publish this series once a month, so you’re in for a bit of a slow burn. Also, this series will only be available to paying subscribers, since they’re the ones supporting this database development. So if you want to read it, you know what to do!

© 2026 Insight Threat Intelligence Ltd. All Rights Reserved.

This newsletter and its contents are protected by Canadian copyright law. Except as otherwise provided for under Canadian copyright law, this newsletter and its contents may not be copied, published, distributed, downloaded or otherwise stored in a retrieval system, transmitted or converted, in any form or by any means, electronic or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyright owner.