Consequences of terrorist listings in Canada

What this means for the Taliban AND ideologically-motivated violent extremists

This post has been sitting as a draft for the last few months. In light of conversations about further sanctioning the Taliban (more on that later) and the takeover of Afghanistan by a listed terrorist entity, I thought it would be useful to go over the implications of being designated a terrorist entity in Canada, looking both at the Taliban and ideologically-motivated violent extremists such as the Proud Boys to illustrate the implications.

Terrorist Listings and the Anti-Terrorism Act, 2001

The Canadian listings process is brought to us by the Anti-Terrorism Act of 2001, and is set out in section 83.05 of the Criminal Code. When it was written, this section was the subject of some controversy, and legal scholars note that the listings process might be “constitutionally suspect”.1 The listing regime first arose following the UN Security Council resolution 1267, which prohibited financial transactions with the Taliban (and Al Qaeda, later) affiliates listed by the Security Council, implemented under Canada’s United Nations Act.2

So what’s an entity?

Only “entities” can be listed as terrorists. An entity can be a person, group, trust, partnership, fund, or an unincorporated association or organization. Organizations are further defined as a public body, body corporate, society, company, firm, partnership, trade union, or municipality, association of persons created for a common purpose, that has an operational structure, and holds itself out to the public as an association of persons.3 So this means that both groups and individuals can be listed as terrorist entities. For instance, we have two individuals listed, Gulbudding Hekmatyar and James Mason, many groups that are commonly identifiable as terrorist groups (like ISIL, Al Qaeda, etc), as well as organizations like the World Tamil Movement and the not-for-profit organization IRFAN.

What remains to be seen is how the listing process evolves with the terrorism landscape. There are currently a number of movements that can be described as extremist in nature4 and whose adherents have engaged in acts of violence motivated by politics, ideology, or religion. For instance, some Boogaloo,5 QAnon6 and Incel adherents have engaged in acts of violence that can be characterized as acts of terrorism. Will we see efforts to list some of these movements as terrorist entities? To my mind, they lack an operational structure. However, the listings process isn’t an entirely rational or a-political process, and it’s unclear if operational structures are a requirement. As such, we may see more listings rather than fewer in the coming months and years, particularly in the absence of any constitutional challenges that force a re-think of some (or all) of these provisions.

Who decides if an entity should be listed?

The ultimate decision to list an entity is the Governor in Council, but that decision is based on a recommendation from the Minister of Public Safety. In order to provide the Minister information upon which to base this recommendation, members of the Canadian security and intelligence community provide information as part of a listings package. This process is usually lead by CSIS or the RCMP, who are the ‘lead pen’ on criminal or security intelligence reports. In some cases, they may draft the listings package based entirely on their own information, or may request or incorporate information from other departments and agencies in Canada, including FINTRAC, CSE, CBSA, Global Affairs Canada, etc.

The threshold for listing is “reasonable grounds to believe” that:

Nomination to be listed

Terrorist entities are nominated for listing in a number of ways. Traditionally, law enforcement and security services consult with the broader intelligence community to determine potential nominees; much of this involves ensuring that the list remains updated with the most recent iteration of a terrorist group’s naming convention. In more recent years, some listings might have come about because of a call for listing in the House of Commons and/or at the direction of Public Safety Canada, which leads a coordinating committee. However, regardless of how they are nominated, evidence of their activities has to be obtained, and that evidence has to amount to reasonable grounds to believe that they have knowingly carried out, attempted, participated, or facilitated a terrorist activity, or knowingly acted on behalf of, at the direction of, or in association with an entity that engaged (or tried to engage) in terrorism.

For example, the Taliban has been a listed terrorist entity in Canada since 2013, but specific sanctions have also been in place under the UN Act (as part of Canada’s implementation of international sanctions against the Taliban) since 1999. On the other hand, the Proud Boys have only been a listed terrorist entity in Canada since 2021. There is a lot of variation in the reasons for listing between these two entities, including the specific use of violence by each group.

The information used for the listings process can be classified or unclassified, although an unclassified summary is always provided on Public Safety Canada’s website. However, the full package of information supporting the listings can be far longer than the public information suggests.

What are the concrete impacts of listing?

When a group becomes a listed entity, the group itself isn’t outlawed, and it isn’t a crime to be a member of the group.7 For the Taliban and the Proud Boys, this means that it isn’t illegal to be a member of the group. However, if an individual’s membership in that group is a matter of public information, further issues might arise for that individual. (More on that in a minute.)

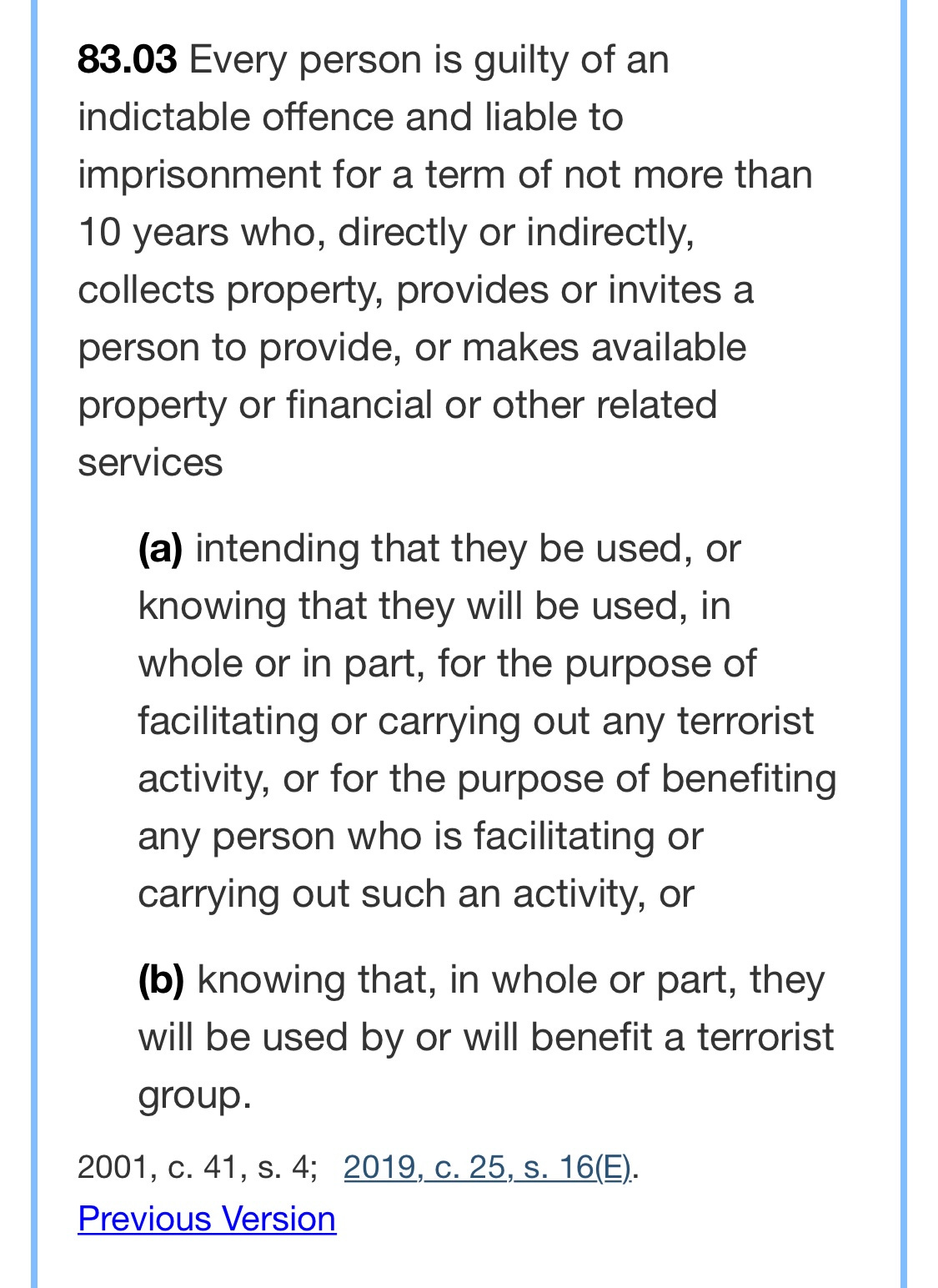

However, it IS an offence to participate or contribute to a terrorist group, either directly or indirectly. BUT this is only an offence if its purpose is to enhance the ability of a terrorist group to facilitate or carry out a terrorist activity.

The criminal code specifies that it’s a crime to provide property or financial services that could benefit a terrorist group. Basically this means you can’t finance a terrorist group but they don’t have to be listed for that prohibition to be in place. And you can’t finance other types of entities if the purpose of that financing is for terrorist activity, but you can provide funds for people or other types of entities for non-terrorist purposes. (This makes some sense - James Mason’s hypothetical employer isn’t financing terrorism by paying him, for example, and donors to a listed charitable organization aren’t financing terrorism unless that organization is a terrorist group, or if the purpose of those funds are for terrorist activity. Still a little fuzzy, I’m sure, and we haven’t even delved into the idea of self-nominating terrorist groups...8)

As Michael Nesbitt notes, the listing process circumnavigates the definition of terrorist activity somewhat with regards to financing a group. The listing process allows prosecutors to rely on the terrorist entity listing without reference to the definition of terrorist activity.9

Upon listing, an entity’s property can be seized, restrained, or forfeited. This means that any accounts held in the name of the Taliban in Canada can be seized, restrained, or forfeited. However, this is unlikely to occur because

a) most terrorist groups don’t actually hold accounts in their names or the names of their leaders, and

b) this is particularly unlikely for groups that operate largely outside of Canada.

Where this has actually been more common is for the listing of organizations (including charitable or non-profit organizations) in Canada. Similarly, it’s unlikely (although not impossible) that the Proud Boys had any accounts at banks or financial institutions that could be seized, restrained or forfeited. The most likely scenario is that a regional chapter of the group might have had a small account at a local financial institution, but even this scenario is fairly unlikely.

At the same time, banks, brokerages, and other financial institutions / entities have to report that they hold terrorist property if they identify any accounts / property in the name of the group, and they can’t allow the entities to access the property. The financial institutions cannot dispose of the property - instead, they essentially have to freeze it.

The law applies to the listed entity, but practically speaking, it extends to individuals associated with it. For instance, if a financial institution like a bank has an account in the name of someone who has been publicly identified as a member of the Taliban, upon listing, they will freeze, seize, and restrain that account or property. Most financial institutions are very risk-averse, and will do this when they suspect that an individual may be a member of a terrorist group. That suspicion is usually based on public information that identifies the individual as a member of the group, and can be obtained through the financial entity’s own social and media monitoring, or through services like Refinitiv World Check / Accelus World Check One.

If individuals are identified as being “associated with” a terrorist group, financial institutions must report any property that they hold to the RCMP, CSIS, and FINTRAC, Canada’s financial intelligence unit, in a terrorist property report.

For the Taliban, it is unlikely that the group had named, publicly-identified members in Canada. For the Proud Boys, the situation is different. There are dozens of individuals in Canada who have been publicly identified as “associated” with the Proud Boys, through attending their protests and rallies, or through social media activity. This means that anyone publicly associated with the group may have been reported to FINTRAC, most likely through suspicious transaction reports. In fact, this is one of the tangible benefits of the listing process. Without being a listed terrorist entity, reporting entities might have insufficient grounds to report a client’s transactions. However, if they become aware of their client’s confirmed or potential association10 with a listed terrorist entity, this usually meets their threshold for reporting.

Concurrently, most banks and financial entities, when confronted with the idea that they may have business dealings with someone associated with a listed terrorist entity, will choose to exit (or “de-risk”) that business relationship. Some of my banking sources tell me that in the case of the Proud Boys, this happened within hours of the listing being made public. This effectively means that they had their accounts frozen, and were instructed to find alternative banking arrangements.

National Security Implications of Listings

For national security and intelligence agencies, the listing process doesn’t do all that much. For investigative agencies, it changes little in their activities. Both CSIS and the RCMP have a mandate to investigate potential terrorist activity regardless of whether the entity the activity associated with is a listed entity. For other agencies, like those primarily involved in analysis or collection (like FINTRAC), but without a broad investigative mandate, this can enable further research, analysis, and dissemination of intelligence, including financial intelligence. The listing process establishes that there are reasonable grounds to believe that an entity is involved (or has been involved in) terrorist activity, allowing some of these organizations more operational space.

In some cases, the listing process may unlock additional resources for investigations, although this is not guaranteed. Further, listings are not required for this - political will is.

The listings process is about trying to ensure that the Canadian financial system isn’t being used by terrorists, but it’s hard to say if that’s actually what’s happening. Financial tradecraft, third parties, proxies, shell companies, and lack of investigative resources assigned to investigate terrorist activity financing all work against this goal.

The Delisting Process

The delisting process is full of mysteries. There is no precise standard of evidence for delisting; instead, it happens on the recommendation of the Minister.11 Historically, only one group (that I recall) has been de-listed, and that’s the Mujahedin-e-Khalq (MEK). When the group was de-listed, the government offered no explanation, but was following the lead of the United States and the European Union who de-listed the group shortly before.

Entities can petition for delisting, but in Canada there has been no successful petition to date. In the case of this process, however, the government could face disclosure implications depending on the type of information that they relied on, and whether it was classified or unclassified, and if classified, if it included only Canadian or allied reporting.

Unfortunately, a lot of information about the listings process is excluded from disclosure through access to information requests due to its categorization as “confidence of the privy council” or as advice or recommendation to the Cabinet or the Minister, as I found out following an access request I placed on the listing of the Proud Boys.12

Other Implications

As noted before, the listings process may be on uncertain ground constitutionally. Further, the listings process can effectively de-bank Canadians; this would happen through Canadian financial institutions identifying a potential association between an individual and a terrorist organization, and refusing them financial services. If all the banks and financial entities in Canada did this, the hypothetical, terrorist-associated individual could effectively be de-banked from the Canadian financial system. However, Canadians have a right to open a personal bank account at a bank (with some exceptions / limitations). It’s unclear how this would work or how an individual could get recourse. I asked the Financial Consumer Agency of Canada for clarification, and they pointed me to the Access to Basic Banking Services Regulations, part of the bank act. In order to refuse to open an account, banks need to have reasonable grounds to believe (note the high threshold of belief) that the account will be used for illegal or fraudulent purposes.

Still have questions about the listings process? Leave a comment and I’ll do my best to update this summary with more information!

Craig Forcese and Leah West, National Security Law, Second Edition (Irwin Law Inc., 2020), https://irwinlaw.com/product/national-security-law-2-e/, 221.

Craig Forcese and Kent Roach, “Yesterday’s Law: Terrorist Group Listing in Canada,” Terrorism and Political Violence30, no. 2 (March 4, 2018): 259–77, https://doi.org/10.1080/09546553.2018.1432211.

Ibid, 216

Stephanie Carvin, Stand on Guard: Reassessing Threats to Canada’s National Security (Toronto ; Buffalo ; London: University of Toronto Press, Scholarly Publishing Division, 2021)., 38

ITAC, “Uniformed Personnel and Ideologically Motivated Violent Extremism” (CSIS, 17 2020). Access to information request courtesy of Stewart Bell.

Ibid

Craig Forcese and Kent Roach, “Yesterday’s Law: Terrorist Group Listing in Canada,” Terrorism and Political Violence30, no. 2 (March 4, 2018): 259–77, https://doi.org/10.1080/09546553.2018.1432211.

Craig Forcese and Leah West, National Security Law, Second Edition (Irwin Law Inc., 2020), https://irwinlaw.com/product/national-security-law-2-e/,

Michael Nesbitt and Dana Hagg, “An Empirical Study of Terrorism Prosecutions in Canada: Elucidating The Elements of the Offences,” Alberta Law Review Society 57, no. 3 (2020), p.23

The term “association” is specifically vague; most financial entities require little in the way of association with a terrorist entity before they decide to de-risk or de-bank a client.

Craig Forcese and Leah West, National Security Law, Second Edition (Irwin Law Inc., 2020), https://irwinlaw.com/product/national-security-law-2-e/, 218.

ATIP 117-2020-S94