Jama’at Nusrat al-Islam wal-Muslimin (JNIM), the al-Qaeda–aligned coalition formed in 2017, has become one of the world’s most dangerous terrorist organizations. Operating throughout the Sahel, the group has doubled the number of attacks it has carried out in 2025 compared to 2024.

We have previously examined JNIM subgroups, with articles on Al Mourabitoun and Ansar al-Dine available on Substack and Katibat Macina included in our terrorism financing case study library. This post provides a standalone overview of JNIM, focusing on developments in its financial profile since 2023. The group’s strength is not only related to its operational tempo, but also to its ability to raise, manage, and obscure funds.

Origins and Operations

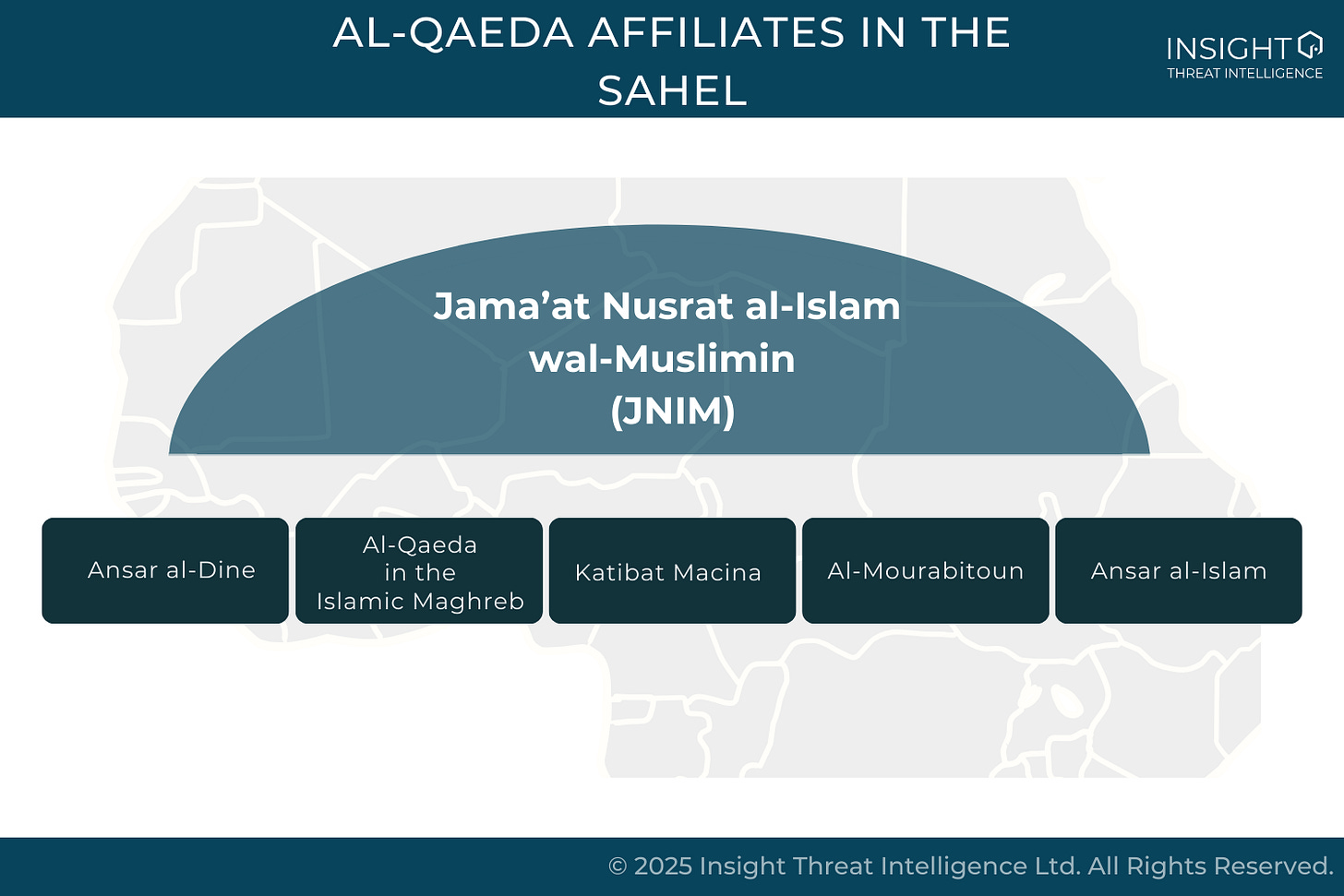

JNIM was created in March 2017 through the merger of several jihadist groups operating in Mali and the wider Sahel: Ansar Dine, Katibat Macina, Al-Mourabitoun, Ansar al-Islam, and the Sahara branch of al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM). The coalition consolidated these different jihadist entities into a unified front, enabling greater coordination, shared resources, and a collective identity under the al-Qaeda banner. Iyad Ag Ghali, a Tuareg former diplomat and rebel, is the leader of JNIM, while Amadou Koufa, a Fulani cleric, is deputy.

As of 2025, JNIM has around 6,000 fighters, making it the largest militant force in the region. Its strongholds stretch from Mali and Burkina Faso into Niger and the Gulf of Guinea states, with Burkina Faso alone recording over 280 JNIM attacks in the first half of 2025. Militarily, the group deploys guerrilla warfare tactics, ambushes, and suicide bombings, often targeting state forces, international missions, and rival jihadist groups such as the Islamic State Sahel Province. Politically, JNIM seeks to build legitimacy in communities by positioning itself as a security provider and enforcer of “justice.”

Raising Funds

JNIM is predominantly financed through local revenue streams as part of the Sahel’s war economy.

Gold Mining

Artisanal gold mining is JNIM’s most profitable sector. The group controls or influences mining sites, regulates access, and taxes production and transport. Within JNIM-controlled areas, artisanal sites can produce up to 725 kilograms of gold annually, worth approximately US$34 million, with primary export destinations in the United Arab Emirates, Turkey, and Switzerland. Revenue from gold mining is not only financial but also strategic: mines serve as recruitment grounds, storage sites for weapons, and logistical hubs, allowing JNIM to secure both resources and social influence.

Kidnapping for Ransom

Kidnapping for ransom has declined slightly as a source of revenue but remains a central element of JNIM’s financing strategy. Between 2017 and 2023, the group carried out 845 of 1,100 recorded kidnappings across Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger. Ransom amounts vary widely: local businessmen can be released for sums as low as $3,000–$5,000, while foreigners can get multimillion-dollar payouts. In 2020, JNIM reportedly secured a ~$40.5 million ransom for the release of one French and two Italian hostages. More recently, reflecting the group’s continued focus on resource extraction, JNIM abducted four foreign nationals in July 2025 from a major cement and lime production site in Karaga.

Our terrorist financing analysis course caters to researchers, intelligence, law enforcement, and compliance professionals to help them learn about terrorist financing, and analyze suspicious patterns and activities more effectively. As part of the course, you receive access to a Case Study Library that contains more group profiles like this one. Sign up today!

Livestock Theft (often reported as ‘Cattle Rustling’)

JNIM has increasingly relied on livestock as a source of revenue, using both theft and coercion. They sometimes raid communities and steal cattle outright, while in other cases they seize animals under the pretense of collecting the Islamic tax (zakat). Unlike traditional zakat, which is intended to help the impoverished, JNIM diverts these resources to sustain its fighters, weapons, and operations. In 2021, the group reportedly generated $739,200 from cattle theft in Mali’s Youwarou district alone, while its subgroup Ansarul Islam earned between US$42,000 and US$50,000 per month through similar raids in other regions. Militants have confiscated entire herds from villages in Burkina Faso, and in central Mali, livestock owners are compelled to give one-year-old bull calves for every 30 cattle and one-year-old heifers for every 40 cattle in exchange for “protection.” Stolen livestock are transported across borders and sold in markets in Mali, Mauritania, or Senegal.

Taxation, Fundraising, and Extortion

JNIM collects zakat and imposes various taxes as part of its broader strategy to generate revenue and assert control over territory. The importance of zakat varies by region: in Kidal, Mali, the group relies more on fundraising than zakat, and contributions are more voluntary in some communities but mandatory for those perceived as “pro-Islamic State”. In central Mali, zakat reportedly constitutes only a minor portion of JNIM’s resources, with roughly two-thirds redistributed to the needy. Regional practices differ widely; in southwestern Tillaberi, Niger, zakat collection is described as “messy and extortionist”, whereas in northern Tahoua, locals perceive it as largely non-violent and limited to traditional contributions.

Beyond zakat, JNIM taxes goods, including fuel, food, and medicines, along major roads and transit corridors in Mali and Burkina Faso, forcibly imposing “protection fees” on merchants, truck drivers, and migrants passing through its territory. Noncompliance often results in the confiscation of goods or vehicles, as evident by one trader whose truck full of tea was seized, taking a year to recover.

Illicit Smuggling

JNIM has embedded itself within broader illicit economies, collaborating with criminal networks involved in drug trafficking, arms smuggling, and human trafficking. While the group often benefits indirectly by taxing or charging fees to traffickers, it also engages directly in illicit activity. For example, it has exploited security gaps in Libya by levying fees on human smugglers forced to use routes through JNIM-controlled territory. In another case, AQIM landed a Boeing 727 full of cocaine (the origin and ownership unknown) near Gao, Mali, burned the plane after unloading, and transported the cargo via trade routes to Libya and Morocco for European markets. It has also leveraged its territorial control to offer protection services to actors involved in illicit smuggling. By 2021, JNIM had expanded its influence across mines, trade and smuggling routes, and large wildlife parks, functioning as a de facto security provider to smugglers, miners, and hunters in exchange for a share of their revenue.

Looting

JNIM diversifies its resources through the looting of military stockpiles, trucks, and the diversion of humanitarian aid convoys. The group frequently targets fuel trucks, sometimes intercepting deliveries suspected to be prearranged by traffickers. Large quantities of fuel are consumed by JNIM fighters, and in some cases, this has reportedly driven up prices, creating more profitable local markets. Surplus fuel is sometimes resold or distributed at below-market prices to sympathetic sellers or communities.

JNIM has also systematically hijacked transport trucks and vehicles carrying a variety of goods along major roadways, including NGO vehicles and ambulances from district health centers. On multiple occasions, aid trucks have been diverted, with food and medicine redistributed to select communities under JNIM control. For example, in April 2022, a convoy of eight new United Nations vehicles bound for Niger was reportedly stolen by JNIM combatants.

Using Funds

Weapons and Equipment

One of JNIM’s main expenses is equipment for its military operations, such as weapons, ammunition, fuel, vehicles, and motorbikes. Motorbikes are particularly valuable in the Sahel’s terrain. JNIM often pre-pays for bulk purchases of new motorbikes from traders who divert them from regional supply chains, frequently through ports such as Lagos, Lomé, and Cotonou. Local dealers describe JNIM as reliable customers who pay upfront and place regular, large orders, ensuring a constant supply. Alongside this investment in mobility, JNIM has also allocated funds toward acquiring and deploying drones, which, when combined with improvised explosive devices and motorbike-mounted bombs, have enabled increasingly complex attacks on well-defended targets.

Consolidation of Territorial Control and Attacks

JNIM carries out systematic attacks to consolidate its territorial control and undermine state authority. The group frequently targets symbols of foreign influence, including French and UN forces, and more recently has threatened Russian mercenaries fighting alongside Malian troops.

To exert control over local populations, JNIM sets up irregular checkpoints where fighters gather intelligence, conduct identity checks for military personnel, state militiamen, and perceived collaborators, and seize vehicles, motorcycles, and other goods to sustain their operations. The group also imposes embargoes and blockades on towns, villages, and entire administrative subdivisions, including the Bandiagara region in Mali and parts of Kompienga, further reinforcing its authority over local communities.

JNIM additionally targets schools and critical infrastructure to weaken state presence and expand influence. Attacks on schools disrupt formal education, replacing secular instruction with religious teachings aligned with the group’s ideology. Roads, bridges, and convoys are also frequently attacked, undermining state capacity while simultaneously creating opportunities for taxation.

Governance and Service Provision

JNIM also channels resources into governance, providing limited but strategic services to strengthen its legitimacy. Despite having relatively low bureaucratic capacity, the group offers basic justice and security functions, including dispute resolution and the management of goods and services from nongovernmental organizations. In some areas, it redistributes zakat revenues to vulnerable populations. JNIM arbitrates disputes, resolves theft cases, and sometimes returns stolen goods, including livestock and items such as telecommunications antenna batteries, to local communities. It has also undertaken initiatives aimed at generating support, such as targeting individuals involved in robberies, gang activity, or other crimes, positioning itself as a more effective authority than weak state structures.

Communications

JNIM allocates resources to enhance both propaganda and operational communications. The group has reportedly acquired satellite internet systems, such as Starlink, to improve battlefield coordination. These systems provide high-speed internet in areas where regular mobile networks are unavailable or unreliable, allowing JNIM to synchronize operations across dispersed units, coordinate attacks, and respond rapidly to shifting security conditions. In parallel, enhanced connectivity supports the group’s propaganda efforts, enabling the dissemination of messages, videos, and ideological content.

Storing and Moving Funds

JNIM primarily relies on cash and in-kind resources, including looted goods, gold, and stolen cattle. Cash reserves are decentralized, with local commanders holding funds to ensure liquidity for ransom payments, supply purchases, and other immediate needs. Mining sites and rural bases also serve as storage hubs for both money and weapons. Funds are moved along routes under the group’s control or, in some cases, through hawala networks. In addition, JNIM invests in small businesses and shops, lends money to merchants, and occasionally uses formal banking systems, embedding itself in local commerce in ways that both generate revenue and strengthen its local legitimacy. Unlike some Islamic State affiliates in the region, there is little evidence that JNIM has adopted cryptocurrency. While ISWAP has reportedly experimented with virtual assets such as Tether, no such activity has been confirmed in JNIM’s case.

Managing Funds

JNIM manages its finances through a hybrid system that combines centralized oversight with local autonomy. The group’s leadership hierarchy is structured around three tiers: central leadership, regional commanders, and local area commanders, anchored by its Majlis al-Shura (leadership council), which sets strategic priorities. High-value operations, such as major kidnappings or international negotiations, typically require approval from senior leaders. Senior commanders are also deployed across regions to maintain cohesion and ensure that local financial practices align with broader strategy, preventing fragmentation. For example, Sidan ag Hitta, sanctioned by the US in 2021, coordinated all JNIM negotiations concerning Western hostages, while Jafar Dicko, sanctioned in 2024, oversaw kidnappings in Burkina Faso through the JNIM-affiliated group Ansarul Islam.

At the local level, JNIM operates on what experts describe as a “franchise model,” adapting its financial governance to regional conditions. This includes tailoring taxation and zakat collection practices to local customs and grievances. In parts of Mali, zakat collection is coercive and deeply resented, while in Burkina Faso and Niger, JNIM has sought to frame contributions as voluntary, redistributing some revenues to local communities to bolster legitimacy. The group also relies on external operatives to sustain its financial and logistical networks. For instance, in July 2024, authorities dismantled a Libyan-led JNIM cell that supplied satellite communication systems and wireless devices to support operations.

Obscuring Funds

Because JNIM controls territory in many areas, it does not always need to conceal its financial activity locally. Operating in a predominantly cash-based economy, JNIM is able to collect zakat in livestock or cash and then pay for goods and services without relying on banks, allowing the group to circumvent the regulated financial system almost entirely.

Concealment becomes more important when funds leave the region or enter the formal economy. To achieve this, the group often relies on intermediaries such as local traders or criminal networks who manage ransom payments, gold sales, or procurement on its behalf. Revenues from gold mining are also laundered through illicit dealers operating in international hubs like Dubai and Turkey.

At the local level, JNIM uses different techniques to disguise or legitimize revenue collection. Payments for access to mining sites or protection fees are frequently framed as zakat, which reduces resistance from communities.

A Shifting Identity?

JNIM is likely to maintain strong financial resilience unless its key revenue streams, including illicit gold exports, livestock markets, and ransom networks, are actively disrupted, all of which would require a significant improvement in governance across the region. At the same time, the group appears to be reshaping its identity. Its congratulatory statement on HTS victory in Syria and the leader’s omission of al-Qaeda in a recent interview suggest a deliberate attempt at rebranding and distancing itself from the global Al-Qaeda network, which it already does not rely on for funding. Looking forward, we will see whether this shift will hold or change the group’s trajectory.

Ultimately, financing in the region remains cash-based and relies on territorial control. Significant improvements in state authority are unlikely in the short to medium term, leaving JNIM well positioned to maintain and expand its operations. The group could also incorporate other groups by offering financial and organizational incentives, further strengthening its power. The security outlook for the region thus remains bleak.

Did you find this post insightful? Share it with a colleague!

© 2025 Insight Threat Intelligence Ltd. All Rights Reserved.

This newsletter and its contents are protected by Canadian copyright law. Except as otherwise provided for under Canadian copyright law, this newsletter and its contents may not be copied, published, distributed, downloaded or otherwise stored in a retrieval system, transmitted or converted, in any form or by any means, electronic or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyright owner.

Excellent work Elena, a real bonus to some CTF work we are starting and very relevant to upstream TF risks we have raised in our UK NRA, thanks