Recently, I read through every FINTRAC report looking for some clues as to the effectiveness of Canada’s counter-terrorist financing regime. While the jury is still out on that question (which also happens to be the subject of my dissertation), the exercise allowed me to pull out some interesting data and points for comparison with this year’s report. This newsletter focuses on that report, but also includes some comparative analysis with prior years. I should note – since my focus is on terrorist financing, I’m largely ignoring a lot of the money laundering information (for now, anyway). Let’s get into it!

Twenty-One Years of Reporting

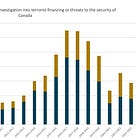

Since its inception in 2000, FINTRAC has put out an annual report every year (except 2000-2001). Reading through twenty-one years of FINTRAC history is an exercise in and of itself, and re-reading the reports from my time there (2009-2013) brought back some very fond memories. It also provides some interesting data that we can use to start to answer the question about what FINTRAC’s role is in Canada’s counter-terrorist financing regime, how it goes about fulfilling it, and how effective it is in that role. While those are some big questions (and well beyond the scope of this newsletter, and probably FINTRAC’s annual report itself), let’s talk about some interesting data from these reports. First of all, there were far fewer disclosures made on terrorist financing / threats to the security of Canada, a level not seen since 2012. Does this mean there is less terrorist financing in Canada than in prior years?

The decrease in terrorism financing and threats disclosures was not due to a significant decrease in reporting to FINTRAC. Overall reports sent to FINTRAC remained about the same, although some pandemic effects were clearly visible in the reporting. For instance, there was a significant decrease in casino disbursement reports, as well as large cash transaction and cross-border currency (and seizure) reports. These types of reports are sensitive to pandemic effects: for instance, closed borders and less travel was a likely causal factor for the decrease in cross-border activity (these reports result from the seizure or declaration of cash in excess of $10,000).

Far less reporting from casinos

Large cash transaction reports also likely experienced a serious pandemic effect with a general move away from cash in the economy (whether this persists in future years will be interesting to see), and of course the closure of casinos, which likely accounts for the majority of the very notable decrease in casino reports. (Casino disbursement reports involve any disbursement of $10,000 or more.) The volume of casino reports was down almost 86% from the year before; casinos were closed for a good part of the year. However, this decline is something that we should keep an eye on, particularly given the Cullen Commission and the issues that were raised with regards to the detection and reporting of transactions from the casino sector.

Less terrorism and fewer threats?

The decrease in disclosures relating to terrorist financing and threats to the security of Canada is one of the more interesting datapoints. This decrease suggests that the Centre is:

receiving fewer financial transactions relating to these threats; and/or

receiving less information from partners in the form of voluntary information about threats (this information helps FINTRAC meet its grounds for disclosure); and/or

having greater difficulty meeting grounds for disclosure for other reasons.

FINTRAC provides financial intelligence to law enforcement (usually the RCMP) when the Centre has reasonable grounds to suspect that the information would be relevant to a terrorist activity financing investigation. Disclosures relevant to foreign intelligence are disclosed to CSE when the information is relevant to the foreign intelligence (interference) aspect of CSE’s mandate, and disclosures are made to CSIS when that information would be relevant to threats to the security of Canada. (Threats disclosures can also be made to law enforcement.)

Together, these types of disclosures are categorized in the annual report as “TF/TH” threats (in blue), and also are also categorized as “TF/TH/ML” disclosures (in brown) when there’s a money laundering component. Categorizing disclosures can be tricky: there are often multiple different activities at play.

This year, disclosures relating to threats and terrorist financing are down almost 51% from the previous years. While these disclosures have been decreasing in recent years (starting in 2017-2018), this is the largest decrease to date. This might be due to a decreasing terrorism threat: my research indicates that terrorist attacks (one measure of levels of terrorism) are down notably, in part due to the pandemic. However, this decrease is curious, particularly in a world of evolving threats like ideologically motivated violent extremism. It makes me wonder whether FINTRAC’s mandate is allowing them to disclose on some of these newer threats, or if there might be a gap or mandate issue.

It's also worth noting here that despite over 4,600 disclosures potentially relating to terrorist financing (this number includes threats disclosures as well), we have had two terrorist financing convictions in Canada. This despite the fact that FINTRAC has written clearly about the terrorist financing threat in Canada in its 2018 report, outlining the various groups that are active in Canada. There’s clearly a discrepancy here in terms of how FINTRAC sees terrorist activity financing and how police are investigating and prosecuting that activity.

For several years now, FINTRAC’s annual reports have emphasized the terrorist activity investigations where their financial intelligence has played a role. For instance, this year, the report noted their contribution to an investigation that resulted in a Toronto-area woman being charged with participation in activities of a terrorist group in Canada.1 While not named specifically, this is likely the case of Haleema Mustafa, who was charged with terrorism-related charges for travelling to Turkey to join the Islamic State – charges that were later stayed. While no details about FINTRAC’s contribution were provided, this could have included suspicious transaction reports (perhaps banks identifying any ATM use in Canada or overseas relevant to the investigative time-period) or international electronic funds transfers of $10,000 or more). This demonstrates that despite the lack of terrorist financing charges and convictions in Canada, FINTRAC’s intelligence is clearly useful for terrorism investigations. However, the full extent of that usefulness remains unclear. Does FINTRAC provide value for its budget in terms of helping to detect and disrupt terrorist financing and threats to the security of Canada? This remains an unanswered question. While we have some qualitative support for the role of the Centre in the form of testimonials from partner agencies, concrete examples of its role and quantitative data showing effects and outcomes remains sparse.

If you want to read about the 2021-2022 report, here you go:

FINTRAC, 9.