The 2025 State of Money Laundering and Terrorist Financing in Canada

A little over two weeks ago, the Government of Canada released its 2025 Assessment of Money Laundering and Terrorist Financing Risks in Canada to very little media attention. But it’s a critically important document for understanding the state of play of how Canada is combating (or not) terrorist financing and money laundering.

What is this?

A National Inherent Risk Assessment on money laundering and terrorist financing is a comprehensive, country-level study that evaluates the main threats and vulnerabilities a state faces from financial crime. The global standard setter for anti-money laundering, the Financial Action Task Force, requires countries to identify, assess, and understand their risks of money laundering and terrorist financing. A risk assessment is the standard method for demonstrating compliance. Without it, states are penalized in FATF mutual evaluations.

Why now?

Canada’s first risk assessment was conducted in 2015. (I was part of the process). Our second one was released in 2023, eight years later. And now we have one in 2025, just two years later. You might be wondering: why so soon for another risk assessment? And the answer is very clear: the FATF mutual evaluation, which is scheduled to take place in 2026. This is part of Canada’s preparation for on-site visits from the FATF (starting this year) that will assess our compliance with international standards, determine what remedies we need to take as a country to meet those standards, and, in the very worst-case scenario, will determine if Canada should be “grey-listed” for lack of compliance with those standards.

Other Effects

While we can cynically discuss Canada’s motivation for this, there are other benefits to this risk assessment:

1. Policy and resource allocation: By knowing where risks are highest, governments can prioritize investigative resources, supervision, and regulatory attention. For example, if real estate is identified as a major ML risk, supervisory authorities can tighten their oversight in this area. (This assumes a government that is willing to tackle illicit finance issues in this country. I have yet to see one elected.)

2. Risk-based approach: Financial institutions and other reporting entities (casinos, virtual asset service providers, money services businesses, etc) are required to apply a risk-based approach to compliance. The risk assessment provides a national benchmark for determining what is considered high or low risk.

3. Foundation for strategy: Many states use their risk assessment to inform their national AML/CTF strategies, legislative reforms, and international reporting. Again, I dare to dream.

How this was reported

Readers of this newsletter will know that I often lament the state of reporting on illicit finance in Canada, and let me tell you, reporting on the risk assessment did not fill me with confidence about the state of our media. The National Post covered the report, but made a significant error when they wrote that CSIS estimated money laundering to be between $45-113 billion per year. It was actually the Criminal Intelligence Service Canada (CISC) that provided this estimate. Very different things, with very different mandates. (I emailed the reported in question, so hopefully it gets corrected soon).

As a sidebar, I wanted to know more about how the CISC estimates money laundering in Canada, so I went to their website to look at their reports….and they aren’t public. I did get a hold of them by emailing (to their credit: they arrived within an hour). This estimate of money laundering in Canada is from the 2020 money laundering report. That estimate, in turn, is based on the UNODC’s estimate that global money laundering is between 2-5% of global Gross Domestic Product. That estimate is based on a 1998 International Monetary Fund Assessment speech (not a report), which suggests that this would be the “global consensus”. If you think this is a dodgy way to create national statistics and estimates, you’re in good company.

As far as I can tell, the National Post was the only Canadian media that covered the report. There were also some mentions in the Jerusalem Post (lamenting our inaction in Hizballah and Hamas) and in the Long War Journal focusing on Hizballah’s use of vehicular theft and money laundering schemes.

Comparative Analysis: 2015, 2023, and 2025

I’m not going to summarize the report: you can do that using your favorite AI summarizer, or just read the executive summary and key findings. Instead, I’m going to focus on a comparative analysis between the three reports, highlighting what’s new, what’s gone, and what it means for the Canadian illicit finance threat landscape.

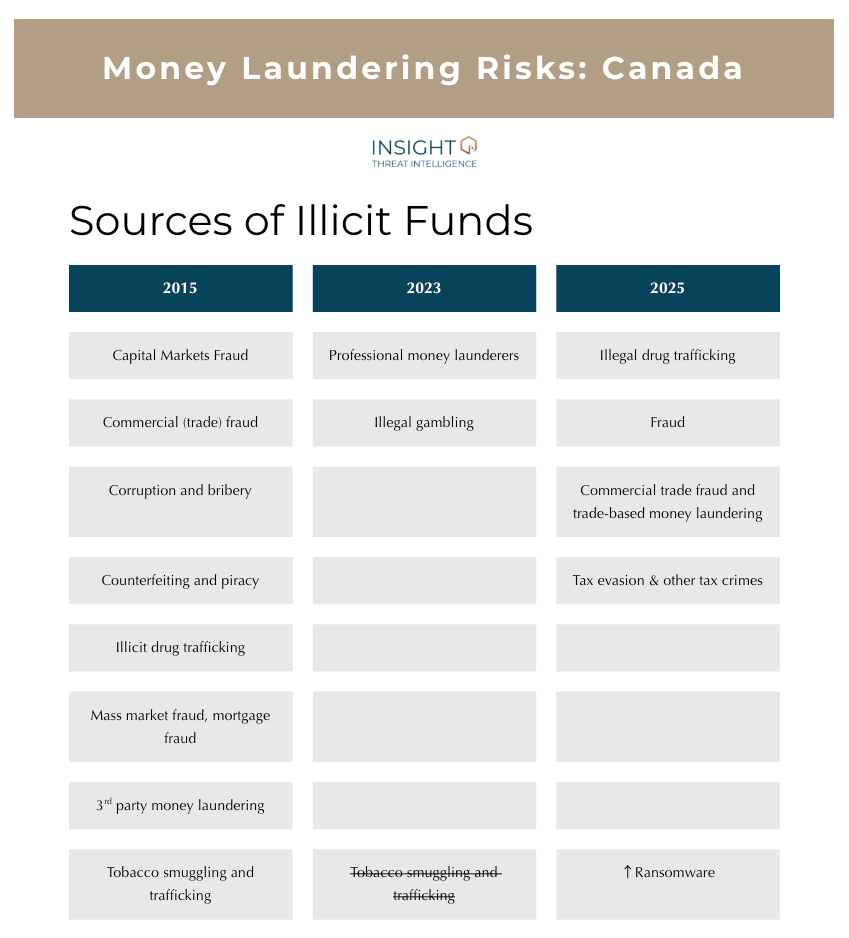

Money Laundering

Over the years, the risk assessments continue to state that billions of dollars of criminal proceeds might be laundered in Canada each year (there’s an element of uncertainty there that I think is important). In 2015, the main culprits were identified as outlaw motorcycle gangs, and professional money launderers. The report also raised a “notable concern” for money laundering associated with the corruption of individuals and the infiltration of private and public institutions. The report also highlighted a series of money laundering threats, illustrated in the graphic below. In 2023, the main culprits of money laundering in Canada were identified as organized crime factions with ties to Italy, Eastern Europe, Latin America, Asia, and some Outlaw Motorcycle Gangs, as well as professional money launderers. Illegal gambling was identified as a new risk.

The 2025 report marks a significant departure in terms of money laundering in Canada. There are significant “success” stories highlighted throughout the report, outlining the disruption and prosecution of money laundering cases in Canada for the last six or seven years. For instance, the report highlights the 2019 success of RCMP Project Collecteur, which was the disruption of an informal value transfer system with connections to Lebanon, the UAE, Iran, US, and China. I have long lamented the RCMP’s inability to tell even a good news story (and of course their challenge with descriptive statistics), so it’s very good to see these mini case studies in this report. It illustrates that, while the RCMP as an institution has challenges, there are bright spots of competence. (It’s also not just the RCMP: other police forces have contributed to these successes as well. Heartening!) In 2025, the threat categories also changed, and there is no longer a “very high” risk of money laundering in Canada.

The report also provides an important update on the expansion of the Trade Fraud and Trade-Based Money Laundering Centre of Expertise, along with the creation of the Border Financial Crime Centre, a new division within Canada Border Services Agency, which includes a new trade transparency unit a new cadre of regulatory investigators. This is an important step forward: Trade-based money laundering is the process of disguising the proceeds of crime by manipulating trade transactions—such as misinvoicing goods, falsifying shipping documents, or over/under-valuing imports and exports—to move and launder illicit funds. Trade Transparency Units are specialized government offices that analyze trade data (often comparing import/export records between partner countries) to detect anomalies and red flags indicative of TBML.

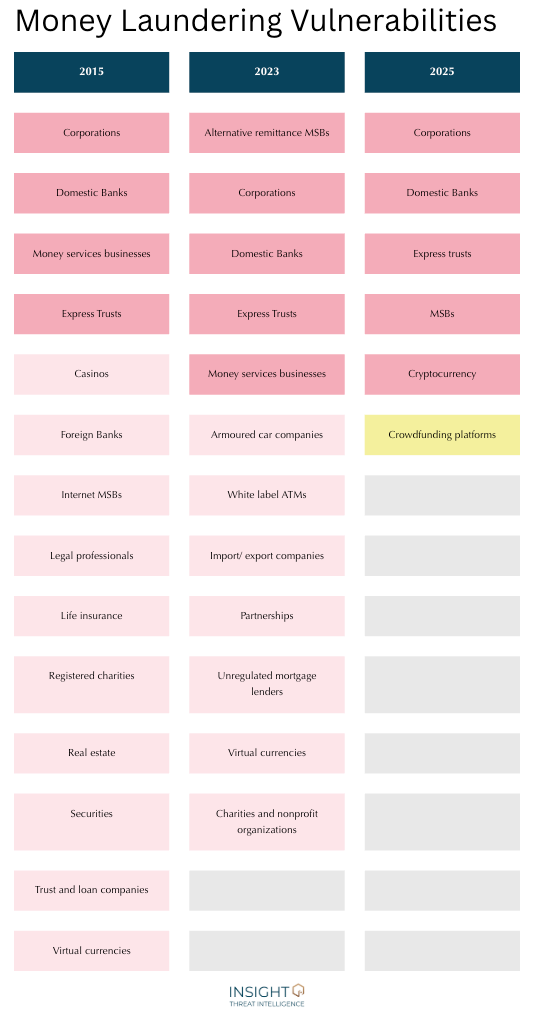

The graphic below highlights key changes between the three reports on sources of illicit funds (methods that create proceeds of crime that need to be laundered) and Canada’s main money laundering vulnerabilities. While these risks have remained fairly constant over the years, 2025 identified a growing issue with money laundering associated with ransomware and new vulnerabilities with cryptocurrencies and crowdfunding platforms.

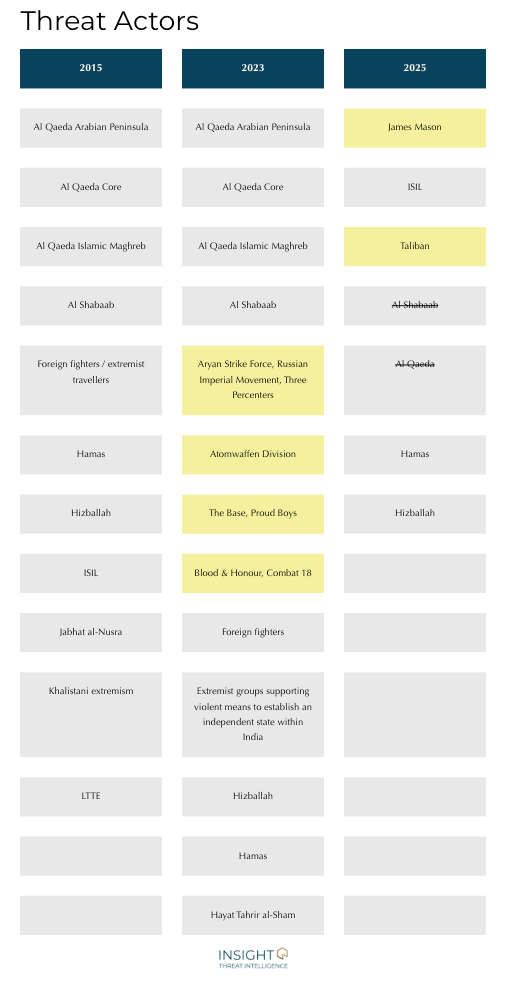

Terrorist financing

In 2015, the risk assessment identified terrorism as the leading threat to Canada’s national security. Methods are identified each year (although I will note that they sometimes confuse sources and methods, such as in 2025, when they discuss state sponsorship as a method of financing, but it’s actually a source. The method would be how the funds are actually transferred.)

There were significant changes to the 2025 section of the report on terrorist financing. First, there is no list of jurisdictions of concern. While I understand that any jurisdiction can be one of concern for terrorist financing (especially when you consider ideologically motivated violent extremism), this list of jurisdictions is one way that reporting entities identify suspected terrorist financing. Identifying suspected terrorist financing in financial transactions is notoriously difficult (what I call a “small data” problem because there are so few transactions that it is difficult to train algorithms or other detection mechanisms, so jurisdictions of concern are an important contribution to establishing grounds of suspicion). The report also breaks the terrorist financing threat into different categories (ideologically, religiously, and politically-motivated terrorism), the same way that CSIS breaks down the threat.

I will admit that I was pretty excited to see references to not only my lawfare article on understanding Taliban finance, but also to two Insight Monitor articles on ISIL in Africa and Hamas financing. This section also highlights two terrorist financing charges: one against Oumaima Chouay (which was later dropped), and also Khalillah Yusuf (to which he pleaded guilty earlier this year). These inclusions are important because they will be relied upon to explain to the FATF how Canada is not just technically compliant with their recommendations (i.e that all the right laws and regulations are in place) but that we are also effective at disrupting terrorist financing. It remains to be seen if FATF will be impressed with our prosecution statistics. (Four successful terrorist financing convictions, and one for financial facilitation).

The 2025 report was also notable because it mentions the Taliban as a terrorist financing risk in Canada. It’s curious that its taken this long to have a mention.

This year there was also mention of foreign interference financing in the report, where they describe money laundering techniques being used to obscure the origin of funds from state actors, and highlight the role of politically-exposed persons who might be vulnerable to being exploited for this activity. As you’ll recall, I highlighted this issue in my report to the Public Inquiry Into Foreign Interference.

What will FATF think?

Canada’s 2025 risk assessment makes a clear effort to demonstrate disruption and prosecution, even if the underlying numbers haven’t markedly improved. It offers one of the most comprehensive overviews of our current threat and risk environment to date. But some of the changes, especially those that touch reporting entities, seem more cosmetic than useful. And there are glaring omissions: Türkiye, for instance, remains off the radar as a jurisdiction of concern, despite well-documented terrorist financing and money laundering activities. Still, those gaps offer space for further analysis—and a reason for me to continue writing and advising on this issue, and for reporting entities to ask better questions.

Did you find this article insightful? Please share it with a friend or colleague and help us grow our community!

© 2025 Insight Threat Intelligence Ltd. All Rights Reserved.

This newsletter and its contents are protected by Canadian copyright law. Except as otherwise provided for under Canadian copyright law, this newsletter and its contents may not be copied, published, distributed, downloaded or otherwise stored in a retrieval system, transmitted or converted, in any form or by any means, electronic or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyright owner.