Terror on the Rise: What the increase in terrorism charges in Canada can tell us about the threat

The terrorist threat in Canada has rarely been higher

The terrorist attack in New Orleans this year has reignited the discussion about terrorism in the US, and, by extension, Canada. Some media outlets have talked about the return of ISIL (they never went away), while some experts have talked about the complex threat level. I decided to turn to our data to figure out what the terrorism threat looks like in Canada.1

For the last six months or so, the team at Insight Threat Intelligence has been working on building a few different datasets. You’ve seen the results of some of these: we’re now able to release data on trends in terrorist financing methods, as well as data about terrorist incidents in Canada. Today, we’re releasing data on terrorism charges in Canada. This data is still preliminary, and we’re continuing to add to it. However, in the context of a spate of arrests at the end of 2024, we thought providing additional context with this data would be useful.

The bottom line: Terrorism in Canada is on the rise, illustrated by increasing attacks and charges and fueled by a volatile mix of geopolitical tensions and growing radicalization across ideological lines.Terrorism charges in Canada are an important indicator of the terrorist threat in Canada. Terrorist incidents (attacks, travel) provide some insight into the terrorist threat, but disrupted terrorist activity, often represented by terrorism arrests and charges, offers additional insight into terrorist activity within our borders. This information can help us understand where our counterterrorism efforts are succeeding, where they are falling short, and what more needs to be done.

The Data

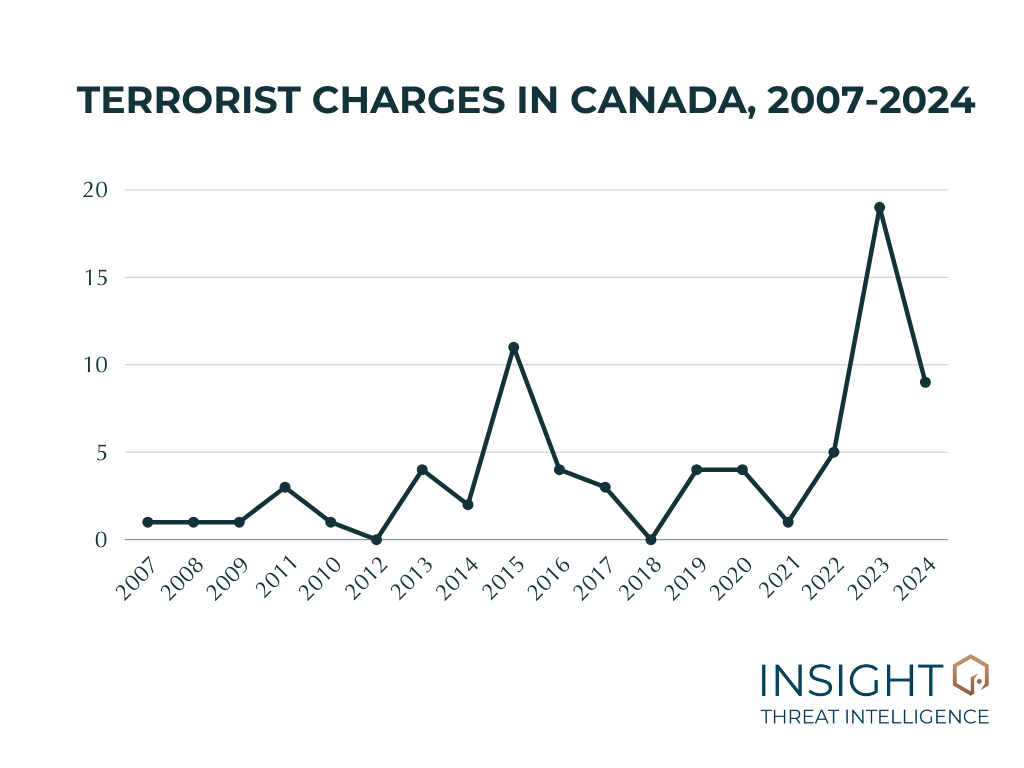

Between 2007 and 2024, there have been 73 terrorism charges in Canada.2 (I started my analysis after the anomalous year of 2006, in which the “Toronto 18” were charged.) Since 2007, there has been a statistically significant increase in terrorism charges, illustrated in the figure below.3

Find out more:

During this time, fourteen of these charges were peace bonds. Peace bonds are a tool available to police in Canada to prevent individuals from engaging in terrorist activity. For more information about peace bonds and a lively discussion on the pros and cons of this tool, have a listen to this Intrepid Podcast episode.

Peace bonds have increasingly been used in terrorism cases in Canada in recent years. There were 2 in 2015, one in 2021, 8 in 2023, and 3 in 2024. However, the utility of peace bonds to prevent terrorism is contested. For instance, Aaron Driver, a Canadian who tried to perpetrate a suicide terrorist attack inspired by ISIL, was subject to a peace bond at the time of his attack.

Terrorist motivation: Political, religious, or ideological?

These data become more interesting when you look at terrorist motivation for charges compared to attacks.

A quick reminder of how we define terrorist motivations:

In Canada, and according to the Criminal Code of Canada, (the main governing legislation for counterterrorism in Canada) terrorist activity has to be motivated by political, ideological, or religious purposes. Because these terms have not been defined in Canadian law, I use the definitions developed by Nesbitt, West, and Amarasingam. Terrorism motivated by a “political “purpose, objective or cause” exists where a group or individual is compelled to act by a desire for their government, a representative of government, or an elected official to take positive action on any matter related to the machinery of government, state, or policy, including economic policy.” Terrorism motivated by ideology requires that “one’s actions or beliefs are driven by a principle or set of unshakable beliefs derived from a scheme of ideas related to society (but not politics or religion).” Explained further, the political motive speaks to “the purpose of compelling a government…or an “international organization” from taking or refraining from taking an action.”4

To illustrate more concretely:

Quebec separatists, Armenian separatists, the LTTE, and Sikh extremists advocating for a Khalistani state are all politically motivated violent extremists (PMVE).

Jihadist groups are religiously motivated violent extremists (RMVE).

Anti-abortion violence and gender-motivated violence are categorized as ideologically motivated violent extremism (IMVE).

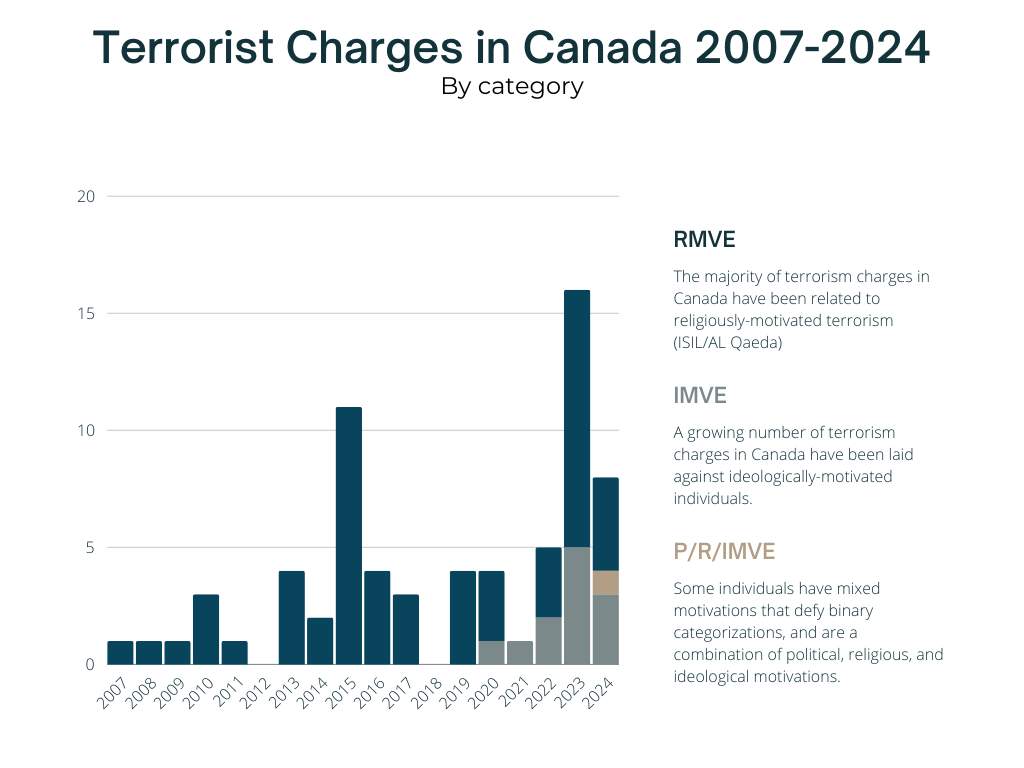

Over the last 18 years, terrorists with a religious motivation have primarily been the ones charged in Canada. However, over the last four years, there has been an increase in diversity of motivation, with ideologically motivated individuals also being charged with terrorism offences, illustrated in the figure below.

Contrast this with attack data for the same time period. Between 2007 and 2024, the vast majority of terrorist attacks in Canada were perpetrated by ideologically motivated terrorists, with only a handful of politically motivated attacks and a few more religiously motivated attacks, illustrated below.

Since 2007, we have seen a statistically significant rise in the number of charges along with an increase in the number of terrorist attacks and people killed in those attacks. However, Canada’s counterterrorism police are far better at disrupting religiously motivated terrorism than ideologically motivated terrorism, illustrated by the disparity in charges between the two categories, as well as by the disparity in completed attacks. This likely has to do with preconceived notions of what constituted terrorism in Canada (Al Qaeda and ISIL were obviously terrorists, but Incel or gender-based violence was only recognized as terrorism more recently). It likely also has to do with international cooperation and intelligence sharing, priorities of our allies, lead intelligence, and the very nature of the threat.

Our terrorist financing analysis course caters to researchers, intelligence, law enforcement, and compliance professionals to help them learn about terrorist financing, and analyze suspicious patterns and activities more effectively. Sign up today and take advantage of an incredible learning package to transform your understanding of terrorism.

Understanding the threat

Charges and attacks are not the only indicators that can inform our understanding of the terrorist threat. In Canada, immigration proceedings are an important part of how we disrupt terrorism. (We will release data on this soon.)

Another indicator of the threat in Canada is arrests and prosecutions of Canadians for terrorism offences in other countries. Canadians have frequently been arrested in the United States, Canada, as well as other countries such as Syria, Kenya, and Kuwait. As many might remember from the El Bahnasawy or the Abdullahi cases, it’s not unusual for the United States to prosecute terrorist activity that occurred, at least in part, in Canada or the United States. Again, we’re still building this data and will share it when we have validated it.

What does all this mean about the threat of terrorism in Canada? The numbers aren’t good. Across the board, terrorism attacks and charges have increased in this country over the last 18 years. While terrorist charges can also indicate a decreasing threat (because of the disruption of terrorist activity), the underlying conditions leading to these charges (and corroborated by the increasing number of terrorist attacks) suggest that the terrorist threat in Canada is high and has rarely been higher.

Geopolitical factors also contribute to this high threat. Across the political and ideological spectrum, extremists are emboldened and motivated to act. From the war in Gaza and recent events in Syria to political polarization in the United States and here at home, all of these factors contribute to the number of people who are radicalized. States have also been emboldened by the conflict to support (covertly or overtly) terrorist groups. While not everyone who is radicalized will engage in violence, by increasing the base rate of radicalization, we inevitably have a larger number of people who might act on their violent ideas. And we have seen the result of this in Canada, which raises concerns for what 2025 will hold.

Did you find this article insightful? Please share it with a friend or colleague and help us grow our community!

© 2025 Insight Threat Intelligence Ltd. All Rights Reserved.

This newsletter and its contents are protected by Canadian copyright law. Except as otherwise provided for under Canadian copyright law, this newsletter and its contents may not be copied, published, distributed, downloaded or otherwise stored in a retrieval system, transmitted or converted, in any form or by any means, electronic or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyright owner.

The fact that we have had to spend months (and soon, years) compiling data on terrorism in Canada illustrates how poorly our government shares information with Canadians. These data are not available from the Public Prosecution Service of Canada or the RCMP. I didn’t even bother asking for data through ATIP because I still have outstanding requests from 2019. It’s hard to make effective policy when basic descriptive statistics of what’s happening aren’t available.

This dataset builds on the important work of Michael Nesbitt in: Michael Nesbitt and Dana Hagg, “An Empirical Study of Terrorism Prosecutions in Canada: Elucidating the Elements of the Offences,” Alberta Law Review Society 57, no. 3 (2020).

This excludes charges that were stayed or withdrawn.

Michael Nesbitt, Leah West, and Amarnath Amarasingam, “The Elusive Motive Requirement in Canada’s Terrorism Offences: Defining and Distinguishing Ideology, Religion, and Politics,” Osgoode Hall Law Journal 60, no. 3 (2023): 580.)