The Axis of Illicit Finance: Iran’s Crypto Strategy Explained

Part 1 of a new 8-part series on Iran's use of cryptocurrency for sanctions evasion

This article marks the start of an eight-part series examining how Iran has increasingly relied on cryptocurrency to circumvent international sanctions.1 These developments unfold against a volatile backdrop: Iran’s 2025 confrontation with Israel, the ongoing activity of its regional proxy network, and protests driven by corruption, economic hardship (exacerbated by sanctions), and political repression. Understanding how and why Iran uses cryptocurrency in its sanctions evasion strategy is essential for anticipating how it could adapt to future countermeasures and what that would mean for global security. Iran’s crypto activity is also part of a broader story. It sits within what I describe as the “axis of illicit finance”: an emerging alternative financial system involving other sanctioned or adversarial states, such as Russia, Venezuela, and the DPRK, with China playing a key supporting role. Over the coming installments, this series will unpack how this system operates, who benefits from it, and why it matters now more than ever.

Iran’s Sanctions Context

Iran has long employed adaptive financial strategies to mitigate the effects of international sanctions and continue backing its regional proxy organizations, including a shadow shipping fleet, money service business and front company networks, and cash couriers. As sanctions have restricted access to formal financial systems, Iran and its affiliates have increasingly relied on cryptocurrency to bypass controls and send funds to the Axis of Resistance, including Hizballah, Hamas, Ansarallah, and Iraqi militias. While Iran’s cryptocurrency-based financing infrastructure remains under development, it continues to advance in sophistication and scope, integrating legacy financial systems with emerging digital mechanisms. It is also increasingly part of an alternative financial systemformed by Russia and the DPRK, and supported by China and used by other countries, including Venezuela. As a result, cryptocurrency is likely to constitute an increasingly significant component of both Iran’s efforts to withstand sanctions and its ability to underwrite proxy activities region-wide.

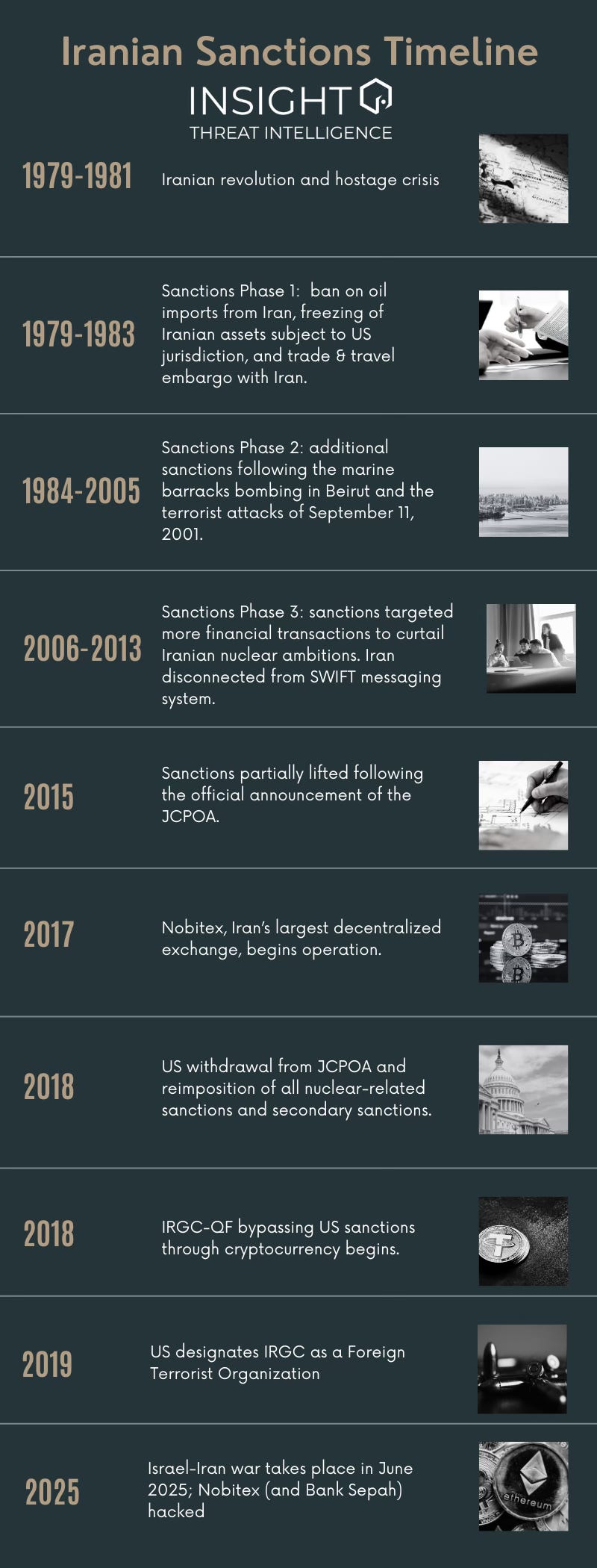

A State Shaped by One of the World’s Most Comprehensive Sanctions Regimes

Since the 1979 revolution, Iran’s economy has repeatedly been hit by international sanctions. These measures are designed to restrict Iran’s access to the US dollar and to US financial institutions, as well as to foreign banks with correspondent relationships in the United States, thereby limiting its ability to conduct trade and international transactions. At various points, the economic impact of these sanctions has been compounded by volatility in global oil prices.2 In other cases, US and international sanctions have prompted Iran to make concessions during negotiations aimed at constraining its nuclear capabilities and development.3 However, under conditions of maximum pressure, these sanctions have also spurred the Iranian regime to intensify its efforts to evade them—both to bolster its negotiating leverage and to mitigate the economic impact at home. Increasingly, these efforts have incorporated cryptocurrencies.

To finance its proxies and evade sanctions, Iran operates a parallel financial infrastructure comprising a network of informal money transfer businesses, bank accounts, and front companies, all designed to launder the proceeds of oil sales and create plausible deniability about the origin of the oil. Wherever possible, this network intersects with the Western financial system, facilitating Iranian financial activities globally. For instance, media reports indicate that two financial technology companies, Paysera and Wise, have unwittingly processed payments for the network. Over the last eight years, Iran has also added cryptocurrency capabilities to this shadow banking network.

Serious cryptocurrency activity in Iran took off in the mid-2010s with the launch of Nobitex, the country’s first major crypto exchange. As of 2023, Nobitex was Iran’s largest crypto exchange; Iran also has four other large exchanges: Wallex.ir, Excoino, Aban Tether, and Bit24.cash. Nobitex is deeply embedded in Iran’s traditional payment ecosystem and enables real-time currency deposits, withdrawals, and account verification. Nobitex functions as a full-service financial bridge that allows users to bypass the international banking system, demonstrating “how crypto rails and domestic banking infrastructure can be fused in sanctioned jurisdictions to create resilient, borderless payment systems.” Iranian citizens (and sometimes even regime members) use cryptocurrency as a means of moving capital out of Iran, particularly during geopolitical crises. Even for Iranian citizens not looking to offshore their wealth, many invest in cryptocurrency to protect their assets from the volatility of the Iranian currency and the broader economy.

Iran’s widespread adoption of cryptocurrency is unsurprising: sanctions can spur adoption, especially in regions with high income inequality.4 Indeed, cryptocurrency adoption is influenced by factors such as economic instability and infrastructure availability, and adoption rates are higher in countries with limited access to the traditional financial system.5

Beginning in 2018, Iran has turned to cryptocurrency to evade US sanctions. The IRGC is a key user, leveraging crypto to fund intelligence work and its proxy network across the Middle East, as well as foreign interference efforts such as sabotage, property damage, and possibly targeted killings.

Course Alert: Terrorist Financing Analysis

Our terrorist financing analysis course caters to researchers, intelligence, law enforcement, and compliance professionals, helping them learn about terrorist financing and analyze suspicious patterns to disrupt terrorist activities more effectively. Sign up today to grow your counter-terrorism expertise.

The Iranian state, regime officials, and the IRGC use cryptocurrency to evade sanctions and gain access to international markets. According to one blockchain analytics company, Nobitex, as well as other Iranian exchanges, have used “advanced techniques” to move funds and obfuscate their origin and destination. For instance, Iran uses cryptocurrency transactions to pay for imports that cannot be processed through conventional payment systems and to make up for revenues lost due to sanctions. Further, Iran has specifically legalized cryptocurrency payments for imports to circumvent sanctions and avoid using the dollar.

In addition to cryptocurrency transactions, Iran also uses its oil surplus to power Bitcoin mining, effectively converting energy into cryptocurrency. Given Iran’s extensive use of cryptocurrency and connections through various blockchains to international markets, generating Bitcoin in this way creates liquidity for Iran, revenues that can be used to purchase goods and services, and money it can send to its proxies in its “Axis of Resistance”. Indeed, the IRGC is widely believed to have undertaken extensive Bitcoin mining operations.

Once Iran has obtained cryptocurrency, it uses those funds to finance other illicit activities. This includes financing groups within its axis of resistance that support Iran’s goal of regional hegemony,6 as well as potentially using virtual assets to fund influence operations abroad.7 To date, cryptocurrency transactions from IRGC Qods Force (QF) have been sent to Hizballah, Hamas, and Ansarallah as part of the IRGC QF’s broader financing strategy. Cryptocurrency transactions might have benefited other groups in the Axis of Resistance as well.

Iran’s turn toward cryptocurrency marks the latest evolution in a long-running effort to withstand and circumvent one of the world’s most comprehensive sanctions regimes. What began as a workaround to maintain economic resilience has now become integral to financing Iran’s broader foreign policy aims, particularly the sustainment of its proxy network across the Middle East. As Iran’s crypto-financing infrastructure grows more sophisticated and increasingly interwoven with an emerging alternative financial system involving Russia, Venezuela, the DPRK, and China, the implications extend far beyond Tehran’s borders. The following articles in this series will examine how Iran’s proxies leverage these financial innovations, the specific methods used to move and conceal funds, and the expanding role of China and Russia in supporting and enabling Iran’s alternative financial architecture.

© 2026 Insight Threat Intelligence Ltd. All Rights Reserved. This newsletter and its contents are protected by Canadian copyright law. Except as otherwise provided for under Canadian copyright law, this newsletter and its contents may not be copied, published, distributed, downloaded or otherwise stored in a retrieval system, transmitted or converted, in any form or by any means, electronic or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyright owner.

This research is part of my post-doctoral work funded by the University of Calgary’s Faculty of Law.

Massoud Karshenas and M Hashem Pesaran, “Economic Reform and the Reconstruction of the Iranian Economy,” Middle East Journal 49, no. 1 (1995): 89.

Wendy R. Sherman, “How We Got the Iran Deal: And Why We’ll Miss It,” Foreign Affairs 97, no. 5 (October 9, 2018): 186–97.

Nga Phan Thi Hang, “Sanctions and Cryptocurrency: A Catalyst for Digital Adoption?,” Journal of Financial Regulation and Compliance 33, no. 3 (2025): 406, https://doi.org/10.1108/JFRC-08-2024-0156

“Global Surge: Exploring Cryptocurrency Adoption with Evidence from Spatial Models,” Financial Innovation 11, no. 1 (December 2025): 96, https://doi.org/10.1186/s40854-025-00765-0.

Daniel Sobelman, “Houthis in the Footsteps of Hizbullah,” Survival 65, no. 3 (May 4, 2023): 130, https://doi.org/10.1080/00396338.2023.2218704.

Gonzalo Saiz, “Sanctions in the Virtual Asset Industry: SIFMANet Roundtable Report,” n.d., 2.