Hello Insight Monitor subscribers! It’s the most wonderful time of the year again: FINTRAC annual report season! The Center’s annual report gives us unique insights into the operations of Canada’s financial intelligence unit. This year, there are a number of highlights, such as FINTRAC’s first disclosure to Global Affairs Canada, new data on disclosures and the value of transactions, and, of course, updated data on the reports FINTRAC receives. But one number stands out above the rest—$44 BILLION in illicit funds. What does this staggering figure mean for Canada? Dive in to explore key highlights, in-depth analysis, and insights into one of the country’s most secretive agencies. If you find this article thought-provoking, share it with a colleague—it’s a conversation worth starting!

FINTRAC, in brief

FINTRAC (the Financial Transactions Reports Analysis Centre of Canada) is Canada’s financial intelligence unit. These units are responsible for receiving and disseminating financial intelligence reported to them from banks, money service businesses, cryptocurrency exchanges, real estate brokerages, and more.

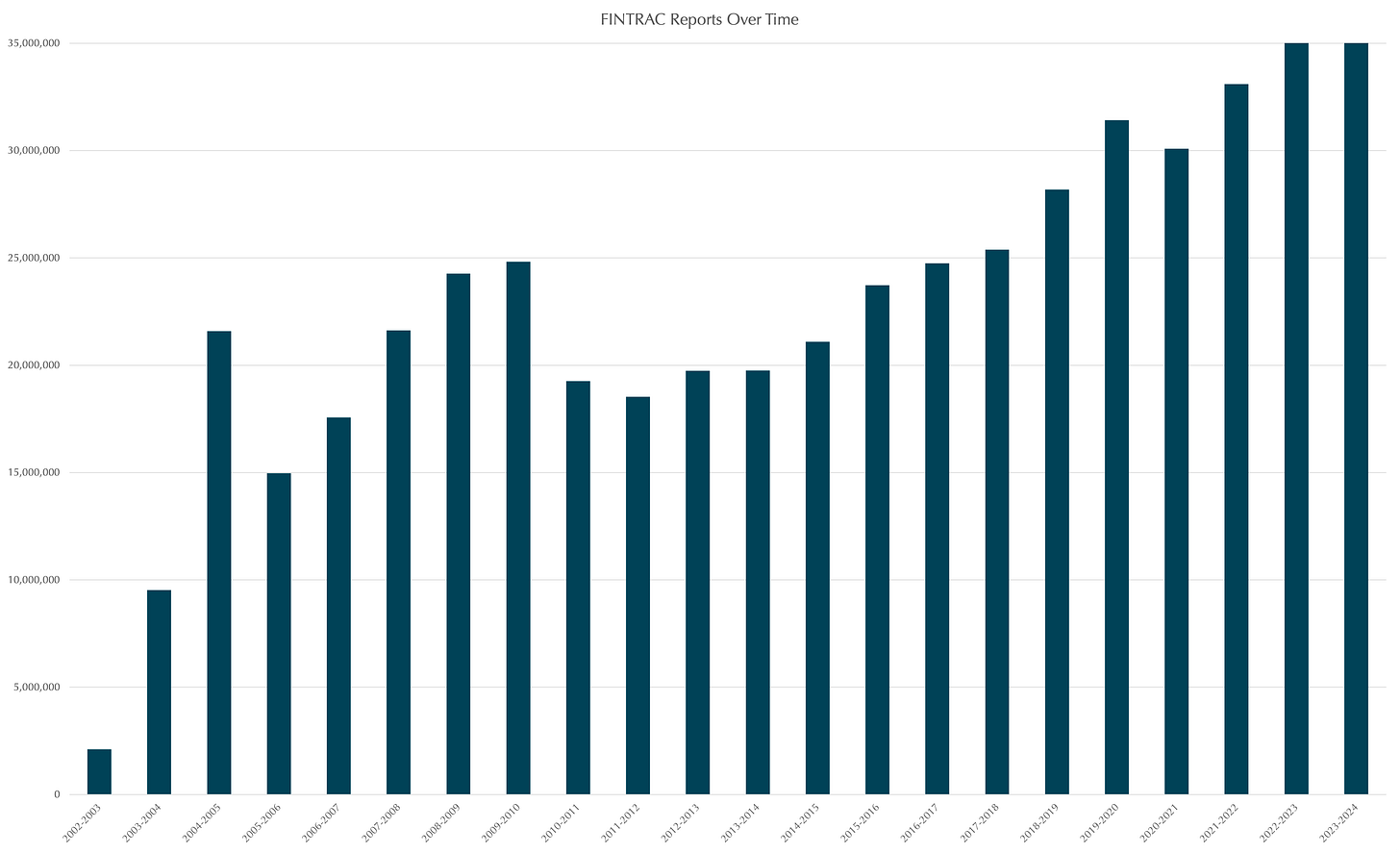

FINTRAC receives a number of “threshold” reports (reports sent to the Centre automatically) of transactions of CA$10,000 or more. This includes reports on large cash transactions, electronic funds transfers (wire transfers), and cross-border currency movements. FINTRAC also receives suspicious transaction reports about suspected money laundering, terrorist financing, and, as of this year, sanctions evasion.

There are different types of financial intelligence units, and Canada’s FINTRAC is an administrative unit: this means that FINTRAC does not conduct investigations. Instead, FINTRAC provides transactions (and some context and analysis) to law enforcement and security services, contributing financial intelligence to their investigations. It’s fair to say that FINTRAC has a finger in almost every law enforcement and security service investigation in Canada.

To learn more about FINTRAC, have a read of the three articles below:

Sanctions Evasion

This year, FINTRAC started to receive suspicious transaction reports relating to sanctions evasion. Prior to this, the Centre was limited to receiving only reports relating to suspected money laundering and terrorist financing. While some sanctions evasion involves money laundering, not all do, so there was a gap in what was reportable to FINTRAC.

While this update only came into force this summer (2024), FINTRAC could disclose information to Global Affairs Canada since last summer (2023). These disclosures relate to the Special Economic Measures Act or the Justice for Victims of Corrupt Foreign Officials Act and related sanctions. This year, FINTRAC sent Global Affairs Canada a single disclosure.

Questions still need to be answered about the utility of these disclosures for GAC, given their limitations on using Canadian information and targeting Canadians for sanctions, since FINTRAC’s data is skews heavily Canadian.

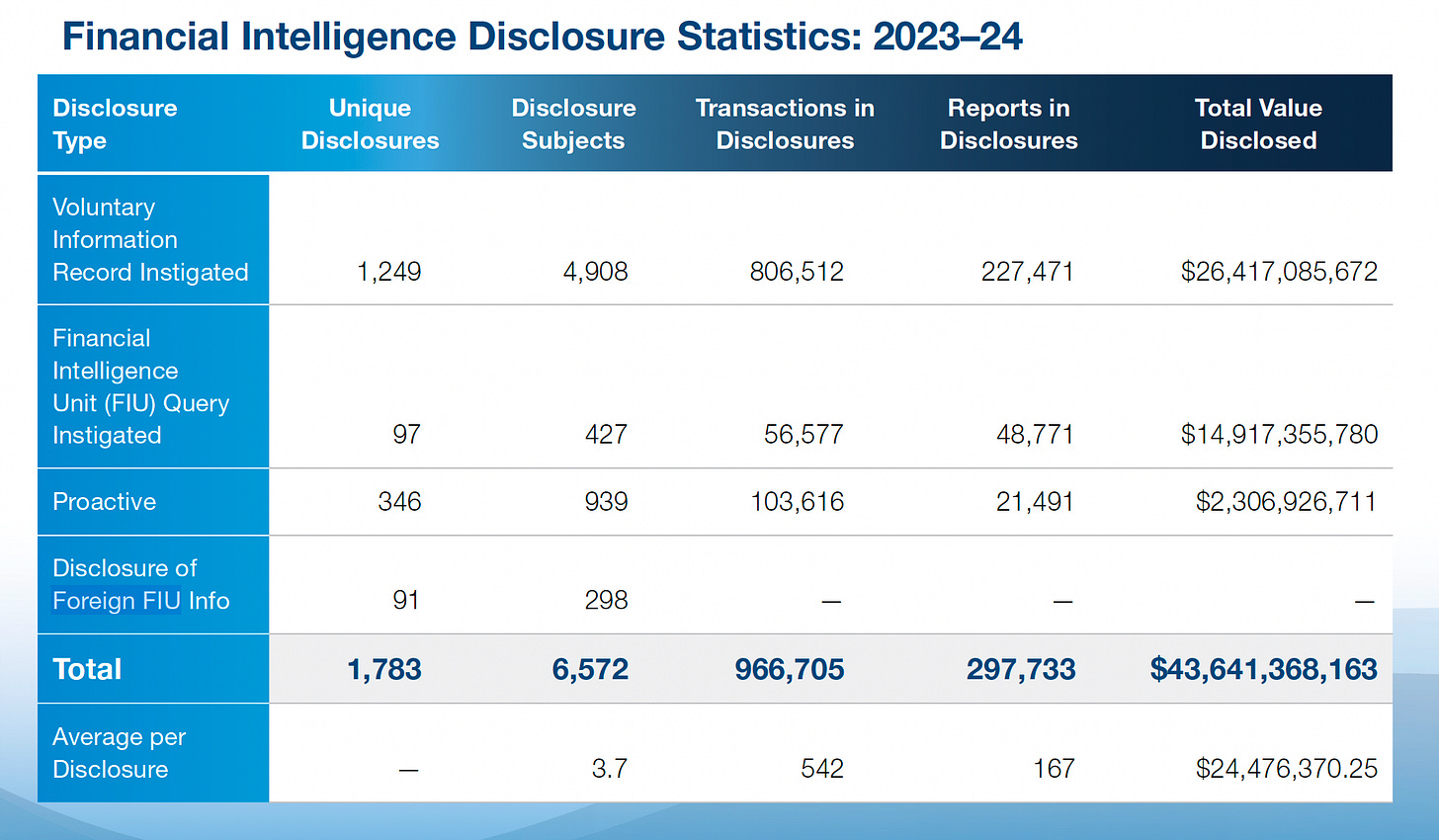

Disclosing the Value of Transactions

In recent years, FINTRAC has come under scrutiny for receiving a LOT of reports but disclosing very few. (For instance: this year, FINTRAC received nearly 49 million transaction reports, and disclosed 966,705, or 2% .) This was one of the criticisms levied at the organization during the Cullen Commission. (You can read what I thought about that here.) In response, FINTRAC has been updating its reporting, and this year, they have included a new table, reproduced below.

This table indicates that FINTRAC has shared a total of 966,705 transactions in 1783 unique disclosures. This is an average of 542 transactions in each disclosure. In total, the value of all transactions disclosed by FINTRAC this year was a whopping nearly $44 billion. That’s $44 billion of transactions that FINTRAC had reasonable grounds to suspect would be relevant to money laundering, terrorist financing, or threats to the security of Canada investigation.

That seems like a lot of dirty money.

Now, to nuance this a bit. First, there is the possibility that some of these transactions have been disclosed multiple times. For instance, a Hizballah financier who is also involved in procuring dual-use technology for Iran and running an illicit money service business in Canada might have their transactions disclosed as possible money laundering, terrorist financing, and sanctions evasion, and those transactions might be included in unique disclosures to three or more different organizations. I asked FINTRAC about this, and they indicated it is possible but rare. Some double-counting might happen in these totals, but it is not enough to shift the scope and scale of the money disclosed.

Secondly, it’s important to remember that these are transactions relevant to investigations of money laundering, terrorist financing, or threats to the security of Canada. That does not necessarily mean these transactions are any of those things. For instance, a terrorism suspect might have all his or her transactions FINTRAC received disclosed to CSIS or the RCMP, but it’s possible that only one or two of those transactions were actually intended for terrorist financing purposes. But all the transactions were relevant to the investigation, so they were all disclosed. Clear?

I think the $44 billion number overstates (possibly by quite a lot) the amount of “dirty” money actually present in those disclosures. I took issue with how similar numbers were represented in a recent op-ed, and you can read some of my reasoning here. However, I also think this might understate the amount of “dirty” money in Canada. FINTRAC only sees a portion of illicit transactions (domestic transactions aren’t reported to FINTRAC unless they’re deemed suspicious, for example), plus, lots of money laundering techniques try to limit what FINTRAC can see. Ultimately, I think we have to be careful about how we characterize these numbers (my clickbait heading notwithstanding) and why a deep understanding of what FINTRAC actually does (and sees) is essential when talking about dirty money in Canada.

For context: If these transactions were contributing to Canada’s economy, illicit finance would probably be in the top twenty sectors contributing to Canada’s GDP.

Terrorist Financing, Money Laundering, and Threats to the Security of Canada

For the first 22 years of its existence, FINTRAC published statistics on the number of disclosures it provided to partners and how those disclosures were categorized (money laundering, terrorist financing, and threats to the security of Canada, or a combination of all three). Then, last year, FINTRAC stopped providing this information in its annual report. I took issue with that then, and I still think this is a big blow to transparency. Not only do these categorizations provide context to the work that FINTRAC is doing, but they are also an important mechanism for holding the RCMP accountable for its responsibilities in investigating terrorist financing, money laundering, and sanctions evasion. We can look at these numbers and ask the RCMP: what are you folks up to? (Hint: the number of money laundering and terrorist financing arrests is not remotely correlated to the number of disclosures the RCMP receives from FINTRAC on these issues.)

Anyway, despite not being provided in the annual report, the folks at FINTRAC were good enough to provide them to me (as they did last year)1. In the chart below, the number of disclosures relating to terrorist financing or threats to the security of Canada steadily increased until 2016-2017, then began a decline. The main pandemic year, 2020-2021, shows the lowest level of these types of disclosures since 2012-2013. Over the last ten years, there has been a statistically significant decrease in the number of terrorist financing and threats disclosures.

There are a number of possible reasons for this. It’s possible that threat actors are using Canada less to conduct their activities, resulting in a decline in reporting from banks and other institutions to FINTRAC and a corresponding decrease in disclosures. It’s also possible that threat actors have gotten better at hiding their activities from reporting entities and FINTRAC and have adopted financial tradecraft to avoid FINTRAC reporting requirements. It’s also possible that FINTRAC has deprioritized terrorist and threat financing disclosures, although, based on my experience working there, I don’t think this is the case. FINTRAC might have also changed how it goes about sharing this information, and instead of providing quick, small disclosures, it provides fewer but more comprehensive disclosures. Finally, it’s also possible that banks and other reporting entities (and FINTRAC itself) are less well-adapted to the current threat environment and less able to detect and disclose terrorist and threat financing activities relating to foreign interference, ideologically-motivated violent extremism and other contemporary threats.

This decline in disclosures relating to terrorism and threats to the security of Canada is surprising, given that reports received by FINTRAC are at an all-time high, as are suspicious transaction reports, illustrated in the figures below.

In my experience, changes in data like this are usually driven by several factors, not just one driver.

The Looming FATF Review

Next year, FATF will start its mutual evaluation of Canada using a new methodology to assess compliance with its recommendations. As part of this methodology, emphasis will be placed on countries posing more significant risks to the international financial systems. Countries prioritized for active review are a) FATF members, b) a high-income country, or c) a country with financial sector assets above US$10 billion. If you’re wondering, Canada fits all three criteria.

The big question is whether Canada will have strategic deficiencies in its ability to counter money laundering, terrorist financing, and proliferation financing. By 2021 (after the initial 2016 review), Canada was found to be compliant or largely compliant across most of the FATF’s recommendations. However, Canada was only partially compliant on recommendations 8, 22, 24, 28, and 29, and non-compliant on recommendation 25.

Whether Canada gets as good a rating as the last follow-up report remains to be seen. FATF is likely looking for progress along many measurable outcomes, and it’s not clear that Canada has made much progress in the last eight years. We’re still waiting for our beneficial ownership registry to come online, for our foreign agent registry, and for the Financial Crimes Agency (remember that?), to say nothing of our dismal prosecution numbers.

At this point, I doubt that FATF will place Canada on the “grey” list for enhanced monitoring, but the new President might be interested in making an example of a G7 country. And if that’s the case, there’s a non-zero chance that example could be Canada. More likely, however, is that Canada is subject to frequent follow-up reports. The folks participating in the mutual evaluation will have a tough hill to climb to demonstrate compliance with FATF recommendations and the effectiveness of Canada’s regime. I wish them all the luck in the world because being grey-listed by FATF would be an absolute catastrophe for Canada’s reputation and economy, particularly with all the global volatility. However, the real travesty is that Canada has not done more to combat illicit finance over the last decade.

Want to learn more about terrorist financing and how to analyze it?

Our terrorist financing analysis course caters to researchers, intelligence, law enforcement, and compliance professionals to help them learn about terrorist financing, and analyze suspicious patterns and activities more effectively. Sign up today and lock in 2024 pricing!

© 2024 Insight Threat Intelligence Ltd. All Rights Reserved.

This newsletter and its contents are protected by Canadian copyright law. Except as otherwise provided for under Canadian copyright law, this newsletter and its contents may not be copied, published, distributed, downloaded or otherwise stored in a retrieval system, transmitted or converted, in any form or by any means, electronic or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyright owner.

I am grateful to FINTRAC for providing this information to me and not requiring a formal access to information request. However, I think that relying on the good will of an organization to provide information is a bad practice for transparency and accountability in Canada. I also think that it’s critical that there’s consistency of data over time so we can actually track changes and progress (or lack thereof). Perhaps something for one of the review agencies, such as NSIRA, or NSICOP, to take up.