Making millions on terrorism? Hamas, short selling, and October 7th

Watching the birth of stigmatized knowledge and conspiracy theories

Welcome to a special edition of Insight Monitor, where we’re looking at whether someone actually made millions short-selling Israeli securities before the Hamas attack. I’m making this article free to read because there’s a lot of misinformation out there that needs to be corrected. Have a read, and let me know what you think in the comments!

The Puzzle

Last week, two US-based researchers published an article “Trading on Terror?”. The authors argue that in the days leading up to the October 7th Hamas attack, there was anomalous short selling on the Israeli stock exchange.

(Short selling is taking a position in the securities market, betting that the price of a security will lose value at some time in the future.)

The authors try to determine who took these short positions, and why.

They put forward two propositions:

That abnormal short selling occurred

That informed traders knew about Hamas’s planned activities and sought to profit from them

(Informed traders are people with more information than the general market participant, and who try to use this information to make a profit.)

Proposition 1: Anomalous short selling

The basis of the research is that a sharp and unusual increase in the shorting of Israeli companies occurred just before the terrorist attacks of October 7th. The authors spend the bulk of their paper demonstrating this anomalous activity. In response to the article, the head of Israel Securities Authorities stated that there were no significant trading abnormalities in the lead-up to the attack.

The authors contend that the unusual short selling is consistent with substantial block trades, and that a small number of actors appear to be behind this options trading.

(Block trades are privately negotiated futures or options that are permitted to be executed apart from the public market)

Israeli authorities further determined that the short position in Bank Leumi (one of the illustrative cases) was actually taken by an unidentified Israeli bank known to the Tel Aviv Stock Exchange (TASE). Finally, whoever carried out these short sells would be transparent to the local regulator because they would have to sign a lending agreement with a TASE member, so the identity of the short sellers is not a mystery.

In brief: according to Israeli authorities, there was nothing anonymous, or puzzling, about this activity.

I find these explanations from Israeli authorities particularly compelling because our political climate is not currently one in which we minimize Hamas’s capabilities.

Proposition 2: That informed traders knew about Hamas’s planned activities and sought to profit from them

Setting aside Proposition 1 for a moment, let’s evaluate Proposition 2 on its own merits.

The authors argue that the most plausible explanation for the anomalous activity is that whoever made the trades was familiar with Hamas’s secrets. They look at pre-incident anomalies and conclude that in October, these anomalies were related to the Hamas attack.

To strengthen this assertion, the authors look at another date (5 April 2023) and find similar anomalies. According to The Times of Israel, this date was the original date of the Hamas attack. This assertion is based on source reporting from unnamed soldiers in the Israel Defence Force’s 8200 signals intelligence unit. The authors conclude that “taken together, this evidence strengthens the interpretation that the trading observed in October and April was related to the Hamas attack rather than random noise.”

I disagree.

General Problems with the Study

There were several general problems with the study that affected its internal and external reliability. Data problems (not understanding that TASE prices are quoted in Agorot, not Shekels) seriously undermine the internal reliability of this paper.

The study was also poorly theorized / conceptualized. There have been few (if any) studies linking short selling with terrorist activity, and certainly very few (if any) studies that suggest that terrorists raise funds in this way.1 The lack of familiarity with terrorist financing literature affects the external reliability of the paper, as well as the general theorizing about what happened, and why.

There were also few, if any, alternative explanations considered and tested. For instance, some critiques have suggested that the anomalies could reflect the closing positions of investors on the first day of a quarter, or that they might have been a market-maker’s response to a trader buying up shares in the fund.

Finally, the type of statistical modelling that the authors use is not particularly compelling for determining correlation. For that, we would need a more robust model controlling for a series of variables as well as seasonality in stock prices and short-selling volumes to determine actual anomalous activity and potentially link it to prior knowledge of a terrorist attack.

The authors essentially identify anomalous activity (proposition 1), and explore one explanation (proposition 2) to explain it. But neither proposition stands on its own, and certainly not taken together.

Finally, the authors do not discuss how the informed traders would come to know about the attack. This would likely occur if the traders were in the inner sanctum of Hamas’s operational planning. Given the closed circle involved in planning this attack, the idea that Hamas would share details of the attack is extremely unlikely, as is the idea that Hamas would encourage informed traders to short these stocks, particularly if it raised the risk of detection.

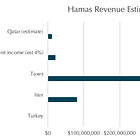

It’s worthwhile noting that Hamas has the financial sophistication to short sells stocks and exchange traded funds in advance of an attack. But they have enough money from other financing activities that doing anything so is not worth the effort, particularly if it raises the risk of detection. And even if they did seek to profit from their attack in this way, they would likely take small positions so as to avoid detection (and avoid creating anomalous data).

The Policy Response

Despite these serious limitations, the authors go on to discuss policy responses. They state that informed traders profited by anticipating the events of October 7th. They suggest that there should be incentives for informed traders to report knowledge of impending terrorist attacks, and that these incentives need to be strong enough to overcome the profit motivation of the informed traders.

They do not, however, discuss how the informed traders might have become aware of a highly secretive terrorist operation, nor do they discuss the viability of encouraging people who might be in the inner circles of terrorist groups to disclose this information to law enforcement and security services. (They put this forward as a potential policy response to this alleged problem, but do not consider whether this is realistic or feasible.)

Ultimately, the authors conclude by saying that “we have provided suggestive evidence that trading on terror occurs through informed trading in securities markets.” I think they’ve failed to both demonstrate that there was anomalous activity, and certainly have failed to demonstrate that its only causal mechanism was prior knowledge of a terrorist attack, or even that this is a viable scenario.

Despite these serious flaws, we all know that this is going to come up for the next decade as “evidence” of terrorist use of securities / options trading. The only value this article has, in my view, is to demonstrate how poorly conceived research evolves into stigmatized knowledge and can become part of conspiracy theories.

Our terrorist financing analysis course is open for the next two months. In February, we’re going to close it to new registrations while we do an update, and re-open sometime in mid-2024. So sign up today if this is on your to-do list for 2023 or 2024! All current students maintain access to course content, forever.

© 2023 Insight Threat Intelligence Ltd. All Rights Reserved.

This newsletter and its contents are protected by Canadian copyright law. Except as otherwise provided for under Canadian copyright law, this newsletter and its contents may not be copied, published, distributed, downloaded or otherwise stored in a retrieval system, transmitted or converted, in any form or by any means, electronic or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyright owner.

Jessica Davis, “Understanding the Effects and Impacts of Counter-Terrorist Financing Policy and Practice,” Terrorism and Political Violence 0, no. 0 (June 9, 2022): 1–17, https://doi.org/10.1080/09546553.2022.2083507.