Rising Threat: The Surge of Ideologically-Driven Terrorism in Canada

From ITI Labs: Data on terrorist attacks in Canada

Hello Insight Monitor subscribers! Welcome to another newsletter dedicated to bringing evidence to the discussion of terrorism. Today, we’re focusing on my home country, Canada. We’re looking at the data we’ve compiled on terrorist attacks. This yields some surprising trends that will almost certainly stimulate debate on what constitutes terrorism and where the biggest threat comes from. Have a read, and let us know what you think!

I’m often asked about terrorism in Canada: what’s the threat? How many attacks do we have? What’s the most serious kind of terrorism? Today, we have (part of) our answer.

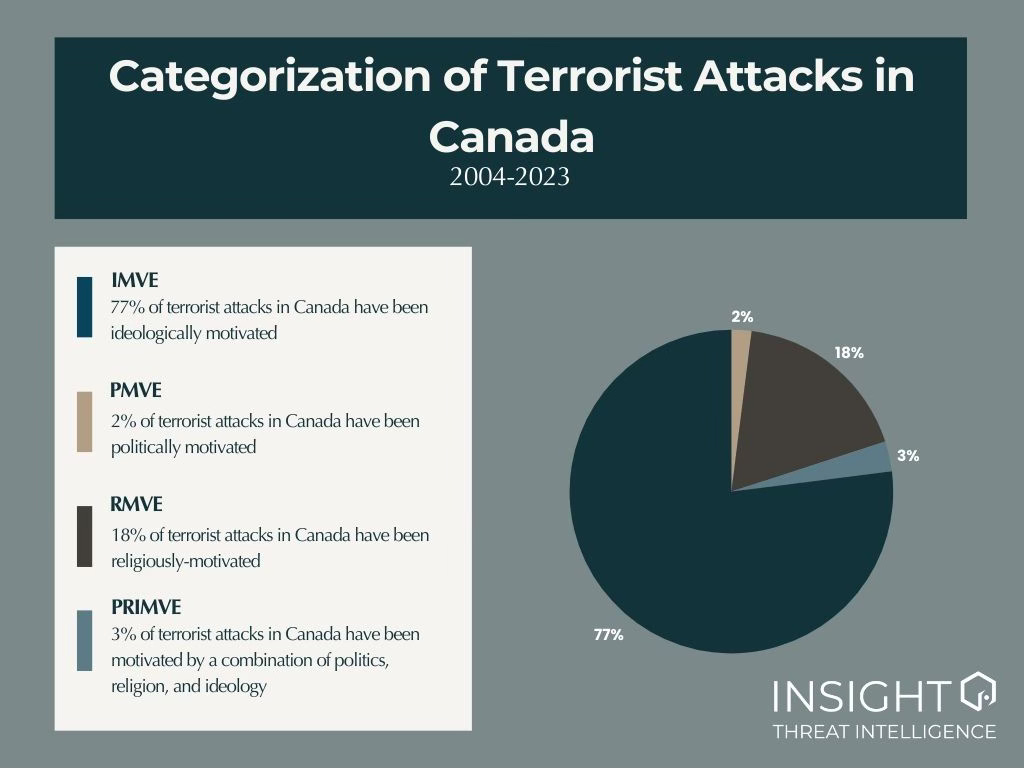

Since 2004, ideologically motivated violent extremists (IMVE) have been responsible for the majority of terrorist attacks in Canada. They have killed 3x the number of people that religiously motivated violent extremists like Al Qaeda or ISIL have killed.

Read to find out more:

These questions might seem straightforward, but when you start to unpack & answer them, they reveal layers of complexity that largely have to do with definitions, data, and measurement. One of the ways I try to answer these questions is by taking the simplest, most observable unit as a place to start: terrorist attacks. Looking at the number of terrorist attacks in a country over a time period doesn’t tell you the full story about terrorist activity or threat, but it is a concrete place to start.

But even then, we must start with definitions: what constitutes a terrorist attack? Because I rely on the Global Terrorism Database for a lot of my academic work, I tend to use a modification of their definition: “the … use of illegal force and violence by a non-state actor to attain a political, economic, religious, or social goal through fear, coercion, or intimidation.”1 In Canada, this is further nuanced by our criminal code definition of terrorist activity, which you can read here.

As part of our data strategy here at ITI, we’ve been creating datasets to answer some of these questions. (You can see another example of our data here, where we talk about changes in terrorist financing trends.) To create the Canada attack data, we used several different datasets, validated their entries, and expanded them to include up-to-date information. We also capture and create several variables other than just the number of attacks and people killed and injured (standard measures in terrorism data). We also look at different types of financing of these attacks (operational financing), which we will discuss in more detail in another article. Our data goes back to 1980, but we are focused here on data since 2004 to keep things contemporary.

Want to learn how to analyze terrorist financing? Our terrorist financing analysis course caters to researchers, intelligence, law enforcement, and compliance professionals to help them learn about terrorist financing, and analyze suspicious patterns and activities more effectively. Sign up today!

The data

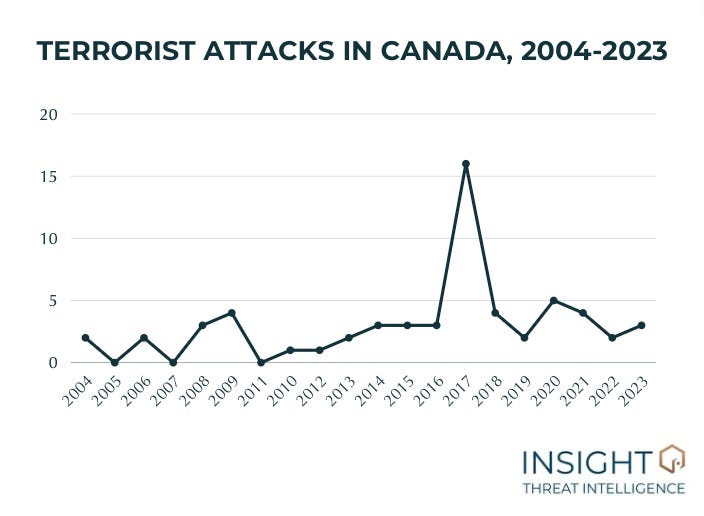

Since 2004, there have been 61 terrorist attacks in Canada, with an average of 3 attacks per year. The number of attacks has been increasing, too.

2017 was a particularly bad year for Canada. There were several attacks including the Rehab Dughmosh attack at Canadian Tire, the Quebec Mosque attack, and a handful of other attacks that received far less media attention.

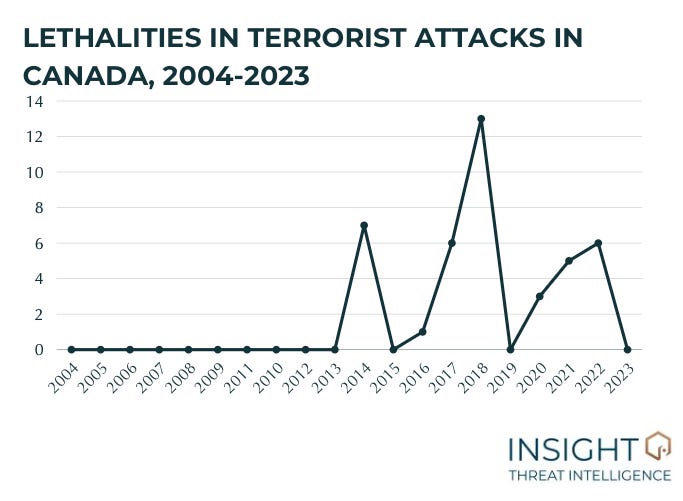

The number of attacks only tells one part of the story, however. I also look at the number of people killed and injured every year. On average, two people are killed in terrorist attacks each year in Canada. Unfortunately, the number of people killed in terrorist attacks has been increasing since 2013.

These attacks can be further categorized by type. According to the Criminal Code of Canada, terrorist activity has to be motivated by political, ideological, or religious purposes. Because these terms have not been defined in Canadian law, I use the definitions put forward by Nesbitt, West, and Amarasingam. Terrorism motivated by a “political “purpose, objective or cause” exists where a group or individual is compelled to act by a desire for their government, a representative of government, or an elected official to take positive action on any matter related to the machinery of government, state, or policy, including economic policy.” Terrorism motivated by ideology requires that “one’s actions or beliefs are driven by a principle or set of unshakable beliefs derived from a scheme of ideas related to society (but not politics or religion).” Explained further, the political motive speaks to “the purpose of compelling a government…or an “international organization” from taking or refraining from taking an action.” 2

To illustrate more concretely:

Quebec separatists, Armenian separatists, the LTTE, and Sikh extremists advocating for a Khalistani state are all politically motivated violent extremists (PMVE).

Jihadist groups are religiously motivated violent extremists (RMVE).

Anti-abortion violence and gender-motivated violence are categorized as ideologically motivated violent extremism (IMVE).

Of course, most attacks and groups have more than one motive. Jihadists are of course motivated by a political project (informed by religion). I try to categorize the attacks as neatly as possible, but there’s always room for discussion and some blurring of categories.

The attacks with an “unknown” motivation were removed from the dataset, as motive is an intrinsic part of the definition of terrorism used in this study. (We still have the data and categorize them as “edge” cases because the motive sometimes becomes clear years later.) One attack in our dataset defied categorization: an individual, angered by the killing of a Hamas leader by the Israeli military, firebombed a Montreal Jewish school, which is simultaneously ideological, political, and religiously motivated (PRIMVE).

Once these attacks are coded, a revealing pattern emerges. Ideologically motivated violent extremists have perpetrated most terrorist attacks in Canada, while religiously motivated violent extremists have perpetrated 18% of attacks. The remaining have been motivated by religion, or in one case, a mix of all three motivations.

This data helps explain why we took a long, hard look at ideologically motivated extremism in our series exploring Canada’s white power ecosystem here at Insight Monitor.

What does this data tell us?

The data reveals a few things, but also raises questions. First, we can see here that the number of terrorist attacks, and the number of people killed, are increasing. This is not good news for Canadians. At the same time, some perspective is important. Canada is still one of the safest countries in the world, and where you’re statistically very unlikely to be embroiled in a terrorist attack. Still, I think we can agree that we would prefer to see these numbers decrease.

We can also see that IMVE attacks are more likely in Canada than RMVE attacks. This likely has to do with the rise of right-wing and other ideologically-motivated extremists like Incels. Indeed, from this data, we can see this rise starting in 2013, while religiously-motivated terrorist attacks start in 2014 in Canada and rise, but not as quickly as IMVE attacks.

As with any data, there are limitations. This data does not include disrupted attacks (plots). We know that Canadian law enforcement and security services regularly disrupt plots through preventative arrests, or other measures, like in the case of the Toronto 18. This is not reflected in this data. If you’re interested in this topic, there’s a great paper on how to integrate plot data into measures of terrorism, and it has informed our own work (more on that later).

It’s also important to note that historical data does not predict future trends. The threat environment is complex: it does not take much for a new type of terrorism to arise, or an old one to become a much more serious threat. This data is just one piece of the puzzle in terms of understanding the terrorism environment in Canada, and we unfortunately can’t use historical data to extrapolate the current or future threat environment.

I can also go into much more detail about the number of people killed and injured in attacks, but given how little data there is here, it’s not worthwhile at this time. That’s the type of analysis that is more useful and yields more results in countries where there are far greater levels of terrorism. So our lack of data is a strength!

Despite the limitations of this data, I think it’s important to ground our understanding of terrorism in Canada in evidence; while we can’t use this data to perfectly set priorities for counterterrorism, it can inform policymakers about the historical threat environment. Couple that data with information on how law enforcement and security services are tackling each type of threat, and you start to get a good picture of where enforcement gaps might exist and need to be shored up.

There are also other data points that can be exploited, like our financing data, and we’ll do that in future articles. What else do you want to know about terrorism levels in Canada? Do you know anyone who would find this interesting? Share it with a colleague and help us grow our community!

© 2024 Insight Threat Intelligence Ltd. All Rights Reserved.

This newsletter and its contents are protected by Canadian copyright law. Except as otherwise provided for under Canadian copyright law, this newsletter and its contents may not be copied, published, distributed, downloaded or otherwise stored in a retrieval system, transmitted or converted, in any form or by any means, electronic or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyright owner.

National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and responses to Terrorism (START), “Global Terrorism Database,” 2019, https://www.start.umd.edu/gtd/about/.

Michael Nesbitt, Leah West, and Amarnath Amarasingam, “The Elusive Motive Requirement in Canada’s Terrorism Offences: Defining and Distinguishing Ideology, Religion, and Politics,” Osgoode Hall Law Journal 60, no. 3 (2023): 580.