Mass murder in Nova Scotia: conspiracy theories and financial intelligence

Two years ago, Gabriel Wortman killed 22 people and injured three others in a two-day shooting rampage in Nova Scotia. The motivations for the attack are difficult to describe with certainty, but his common-law spouse told police that he was consumed by the pandemic, and was stockpiling food and gas and “was preparing for the end of the world.” The inquiry into the events of those two days continues, but I wanted to revisit one particular and disturbing element of the incident that has ongoing ramifications for extremism in Canada: the conspiracy theory that Wortman was a police agent / informant.

On 19 June, 2020, Maclean’s magazine published an article suggesting that Wortman might have been an RCMP agent or informant. The evidence cited for this assertion was the opinion of unnamed RCMP and banking sources, none of whom had direct knowledge of the investigation. These sources said that the withdrawal of $475,000 in cash from his accounts “matches” the method the RCMP uses to send money to confidential informants and agents (cash payments). What appeared particularly suspicious to these sources was that the transaction was conducted through a Brinks depot, not a commercial bank. The assertion that Wortman was a paid RCMP agent/informant morphed into the idea that the RCMP was directly or indirectly complicit in the worst mass-murder event in recent Canadian history. There is no evidence to suggest that this is anything other than a conspiracy theory.

The sources cited in the article asserted that this particular withdrawal method (cash from Brinks) is not available to private banking customers. The unnamed RCMP sources were unequivocal in their assessment of what this transaction meant, stating that there is “no way a civilian can just make an arrangement like that”, that “to me that transaction alone proves he [Wortman] has a special relationship with the force,” and “I think [with the Brink’s transaction] you’ve proved with that single fact that he had a relationship with the police. He was either a CI or an agent.”

As soon as I read this article, I was immediately wary of these assertions. While not naming sources is fairly common (particularly when they’re discussing sensitive information or an ongoing investigation), the absolute certainty that these particular sources expressed was a concern. From my own experience in anti-money laundering / counter-terrorist financing, I know that exceptions to usual banking business practices happen all the time — sometimes for legitimate reasons, and sometimes for nefarious ones. These sources based their judgement that Wortman was an RCMP agent / informant on a single, unusual transaction.

The sources also seemed to ignore important contextual factors. First, the transaction took place in small town Nova Scotia. Most banks in the area would likely have a difficult time coming up with this quantity ($475k) of cash, and banks in general would be wary about providing a customer hundreds of thousands in cash due to concerns about loss or theft, which potentially explains the use of the Brinks depot. The second contextual factor was the pandemic. At the time that the withdrawal took place, the stock market was losing ground rapidly, and there was concern amongst investors that the beginning of the pandemic would also signal the beginning of a market crash or potentially bank runs. These concerns create a plausible reason for withdrawals from investment or savings accounts. The sources also seemed to ignore the possibility that Wortman had significant personal wealth, seemingly fixating on the relatively large sum of money. I was more circumspect: I could see a number of scenarios that would lead to him having this amount of money, ranging from being a good investor to criminal activity (or potentially a combination of the two).

Where that “informant” money really came from

Statements from the RCMP, the disclosure of investigative documents, and the public inquiry into the shooting, indicate that Wortman was not an RCMP agent or informant. As Tim Bousquet reported , the RCMP has repeatedly denied any special relationship with Wortman. Further, we now know that Wortman gained access to this cash by liquidating his investments. CIBC transferred the money to Brinks through its currency service Intria, likely to get around the issues I discuss above (liquidity and security).

CIBC’s corporate security explained the withdrawal of $475,000: they said that Wortman liquidated his assets on March 20th by cashing GICs, and redeemed other investments a few days later. He spoke to the manager at the CIBC where the investments were being deposited after liquidation and arrangements were made to provide the cash through Brinks.

However, that’s not to say that all of these funds were legitimately acquired. Wortman is alleged to have had an extensive criminal career. Suspicious transaction reports dating back to 2010 detail a number of large cash deposits to investment accounts controlled by Wortman. None of his businesses were cash intensive businesses, and the transactions went unexplained.1 While certainly not conclusive, this supports the hypothesis that he was involved in criminal activity. These transactions could also support the hypothesis that he was a paid police agent / informant, but there is no other supporting evidence for this theory, and plenty of supporting evidence for other explanations.

What can Wortman’s transactions tell us?

Following the shooting, Wortman’s transactions were reported to FINTRAC by some of his financial service providers, and others provided information on his accounts. For instance, PayPal submitted a suspicious transaction report after the shooting detailing his online shopping and purchase of police equipment in 2019.

Wortman’s financial transactions were disclosed by FINTRAC, Canada’s financial intelligence unit, to law enforcement, and much of this information was subsequently made public through requests to the inquiry. After the shooting, PayPal reported transactions that occurred on its platform, noting that the equipment (purchased in 2019) could be “utilized in the facilitation of domestic terrorist activities” including materials usually purchased by law enforcement. However, reporting entities are not particularly well-placed to detect pre-attack activity prior to an incident, and PayPal likely had no additional contextual information to make this determination except what had been publicly reported publicly in the wake of the attack. The reporting of suspicious transactions following a violent incident or attack is common practice, as reporting entities often lack the required grounds for suspicion to report seemingly normal (or even somewhat unusual) transactions until an incident occurs.

In hindsight, these purchases, Wortman’s personal finances, and the liquidation of his assets paint a relatively convincing story of mobilization to violence. It’s critical though, when examining financial intelligence like this, not to fall into hindsight bias.

It’s unlikely that these transactions appeared to reporting entities to be anything other than relatively normal financial transactions in the lead-up to the event. While his liquidation of assets could be seen as a preparatory step for mobilization, there is a plausible alternative explanation (market fears brought on by the pandemic). And while the purchase of police-related materials is a clear red flag in retrospect, in practice, there are many law enforcement enthusiasts who collect these type of goods. Without an existing investigation (and in this case, there was none), this financial intelligence lacks important context.

Why the conspiracy theory matters

The Maclean’s article that initially put forward the idea that Wortman could be an RCMP agent/informant came at a time when the community that experienced the attack was already suffering from a low level of confidence in its police services. There were issues with how the incident was handled, as the inquiry is making abundantly clear. But putting forward this speculative assertion that Wortman was a police asset supported only by the opinions of unnamed sources did great harm to the community and their trust in police.

Further, the article remains in circulation, with no correction or retraction, and a quick check of Twitter shows thousands of shares without correction / addendum. And when I speak to people who have read the article, they are astonished to realize that it was written with so little evidence. Macleans is a reputable news source in Canada, so most people take what they publish largely at face value.

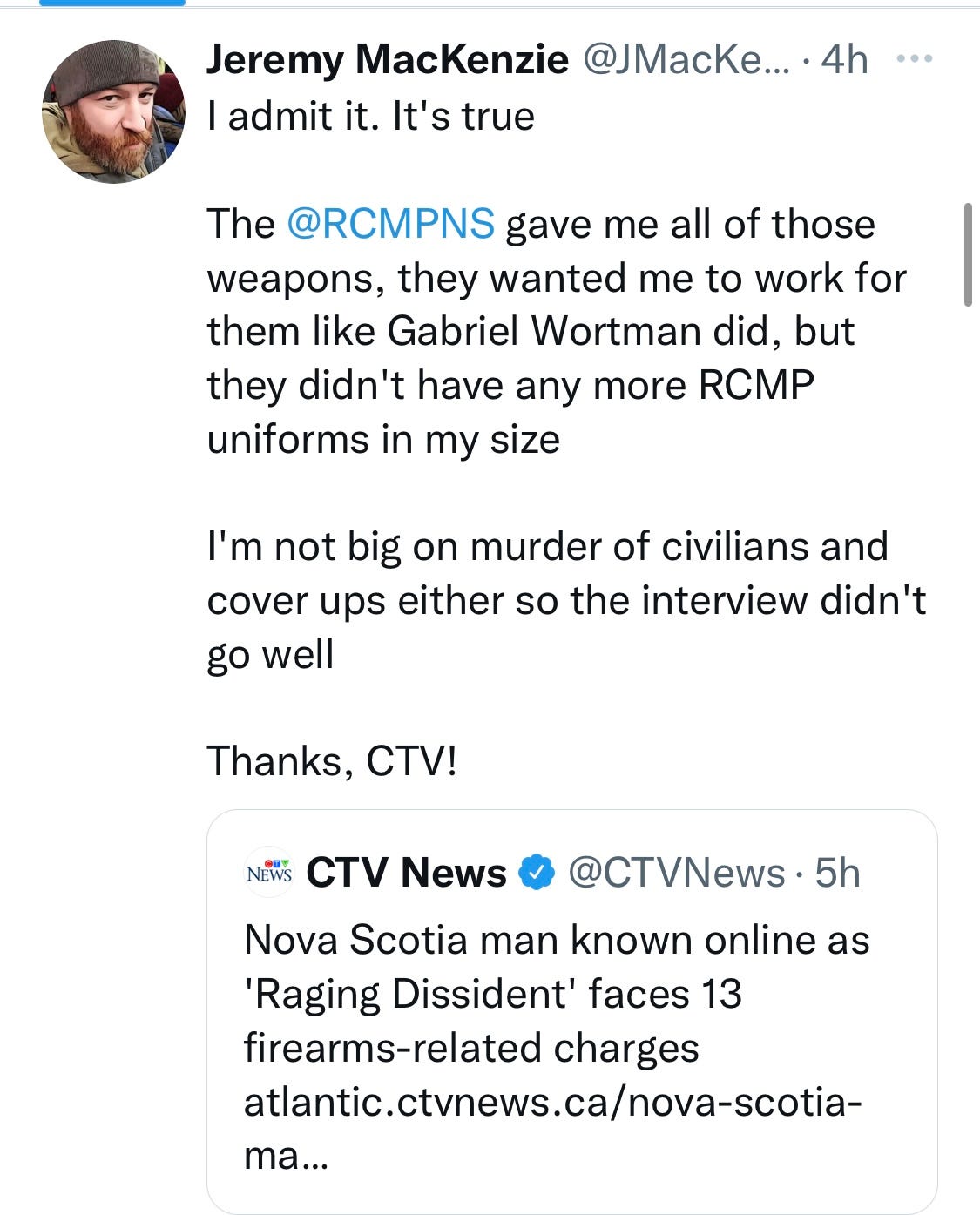

Finally, as Canadian Anti-Hate Network’s Peter Smith explained to me, this conspiracy theory helped catapult a Canadian extremist into virality. Jeremy MacKenzie, a Nova Scotia-based extremist and the creator of the concept of Diagolon, believes his sharing and discussion of Wortman’s alleged relationship with the RCMP was an important moment in his history.

He credits his discussion of the RCMP’s alleged relationship with Wortman with expanding his reach and appeal on social media platforms. He continues to spread the conspiracy theory of Wortman being an RCMP agent.

As we think about trust in government and institutions and the role that conspiracy theories play in undermining that trust, it becomes clear that the media has an important role. Small (and sometimes not so small) mistakes by the media can fuel conspiratorial thinking and are quickly amplified on social media platforms. It’s bad enough that many Canadians believe this version of events, despite strong evidence refuting these allegations. What’s worse is that this story has been used to help launch an extremist’s career.

Want to read more analysis like this? Subscribe today!

This isn’t unusual. FINTRAC receives hundreds of thousands of suspicious transaction reports every year, and millions of large cash transaction reports. Only a small proportion meet the threshold for disclosure to law enforcement and security services. If you want to know more about FINTRAC’s reporting and activities, check out this post.

A co-author of McLeans story you reference is Joe Palango, also the author of a new book on the Nova Scotia events. I have not read the book, but part of its premise goes as follows: "Nova Scotia mass shooting inquiry more about covering up than finding answers, says author Palango" (From Saltwire, Feb. 22/2022) Coverup is in the title of his book. "22 Murders

Investigating the Massacres, Cover-up and Obstacles to Justice in Nova Scotia." Palango, on the basis of zero facts, denounces the public inquiry as a sham, even before it has completed its hearings, let alone reached and published its findings. Palango's book is opportunstic and cynical, and premature--he does not know all the facts. The Mass Casualty commissioners have been given broad powers and from their resumes seem hardly the kind of professionals who would agree to participate in such an exercise if it was a sham. What's more, the Commission is supported by a team of 20-30 professionals expert in the various disciplines needed for such an enterprise. Have all these people been brought into the coverup conspiracy too? Ms. Davis, your article is timely and insightful.